Why Smart Glasses Are Already Dominated by China — Why Even Apple and Meta Have No Choice but to Cooperate

Recently, there was an article like this.

Meta will unveil new smart glasses called Hyper Nova at its annual Connect event on September 17 and September 18.

The prevailing view was that, unlike the previously released Ray-Ban Meta glasses, the Hyper Nova coming this time would have a display and its price would be high—above $1,400.

However, contrary to expectations, according to a report by Bloomberg’s Mark Gurman, it will launch at $800.

Why is that?

I want to find the reason in competition with Chinese manufacturers.

About a month ago, Alibaba released smart glasses called Quark Vision.

But the price is 1,999 yuan, about $280.

So from Meta’s perspective, with China putting products out that cheaply, they might have thought, “How can we charge more than $1,400?” and decided to set a lower price.

I believe smart glasses will become a truly essential device.

Let me give an example. Unlike smartphones, smart glasses are much more convenient to operate.

You don’t even need to move your fingers—you can operate them through humanity’s most concise action: your voice.

For instance, if you were trying to use AI features like Gemini Live on a smartphone, you would have to open the camera app with your fingers and scan things yourself; with AI glasses, however, the camera on the device is effectively seeing what I’m seeing, so there’s the advantage that I don’t have to issue instructions one by one.

This is the industry’s classification of smart glasses by generation.

So far, Meta’s Ray-Ban Meta falls under the first generation of smart glasses.

Now, Meta’s upcoming Hypernova and Alibaba’s Quark Vision are considered part of the second generation.

Starting from the second generation, displays are built in by default, which means AR functions are also supported.

However, the displays are still expected to be low-resolution — mostly monochrome, with some models possibly featuring full color.

That’s why I believe the second generation is the point where we can truly start calling them smart glasses.

From the second generation onward, displays provide visual information, allowing users to access much richer data through the glasses.

To draw an analogy: up to the first generation, they were more like PDAs, but starting from the second generation, they can be called smartphones.

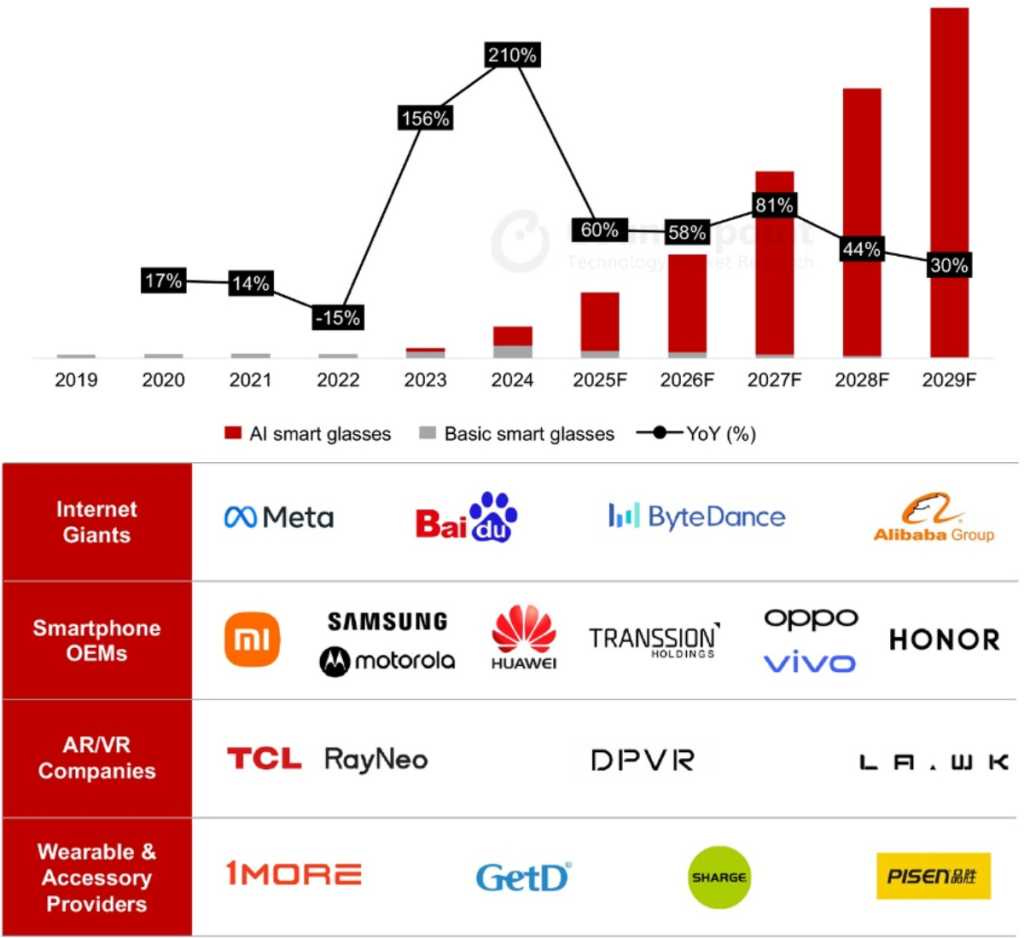

This is data released by Counterpoint Research.

Please note their projection of 60–80% annual growth starting this year.

With so many manufacturers continuously rolling out new products, the market is bound to keep expanding at the same pace.

Here’s a table summarizing smart glasses released since 2018.

Looking at the types of displays adopted by products that have branded themselves as smart glasses, in the early days of this industry, LCoS was the most common. For example, the well-known Google Glass at the time was also equipped with LCoS. Three such models came out in 2018.

Although LCoS has continued to appear since then, it hasn’t really become the mainstream choice. Today, the main display technology in the market seems to be OLEDOS. As you can see here, there are many more models using it, and new ones keep being released every year.

Interestingly, LEDOS was absent in 2018, 2019, and 2020, but starting in 2021, its presence has been steadily increasing.

For now, it looks like the three technologies are still competing, but the key point to note is that LEDOS has been gradually increasing since 2021.

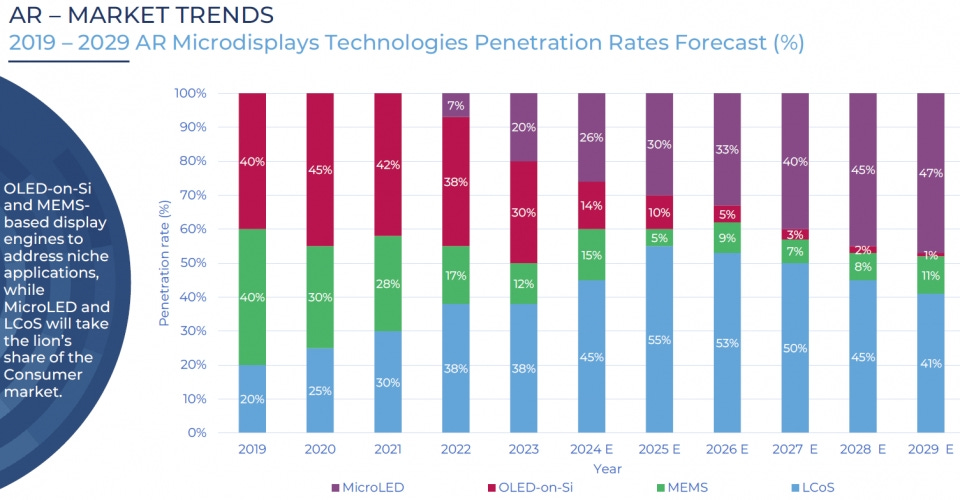

If you’d like to see this more clearly, please take a look at this chart.

Here, you can see the AR glasses market—in other words, the smart glasses segment within the broader AR market—and the penetration rates of each display technology. We’re now looking at this from the 2025 perspective.

As you can see, LCoS currently holds the largest share. However, since 2022, LEDOS has started to enter the market and is expected to steadily expand its presence. Meanwhile, OLEDOS is projected to gradually decline, and LCoS is expected to stagnate.

To summarize: the rise of MicroLED (LEDOS), the decline of OLED-on-silicon (OLEDOS), and the plateau of LCoS.

The reasons behind this trend are as follows.

Here you can see a comparison of the strengths of LCoS, OLEDOS, and LEDOS.

So, what are the most essential advantages required for displays used in smart glasses? In my view, brightness and power efficiency are the most important.

The reason power efficiency is critical should be clear. Since these displays are embedded in glasses, if power efficiency is poor, the product essentially becomes useless. At best, you could only mount the battery in the frame of the glasses, but without achieving low power consumption, it would be impossible to make them practical.

The next key factor is brightness. For VR headsets—like Apple’s Vision Pro—where the field of view is fully enclosed, brightness doesn’t need to be extremely high. Because outside light is completely blocked, the display isn’t affected by external lighting.

But AR is different. If you remember the first Google Glass, it looked just like regular eyeglasses, meaning it is directly exposed to external light. Outdoors, you’re under sunlight; indoors, you’re under fluorescent or other artificial lighting—all of which interfere with visibility. If the display’s brightness is low, then external light overwhelms it, making it hard to see the image clearly.

That’s why I believe these two factors—power efficiency and brightness—are the most crucial. In this respect, LEDOS has advantages, as you can see here. However, it hasn’t been widely adopted so far, likely due to the lower level of technological maturity.

Meanwhile, LCoS has been used extensively because its maturity level is the highest. Being based on LCD, it allows for higher pixel density, decent color purity, and reasonable brightness and power efficiency. While not perfect, it has been the most practical and accessible technology, which is why it has been adopted the most.

Looking ahead, though, LCoS may stagnate, and its place is expected to be taken by LEDOS. That’s the way I would interpret the trend.

Then, if we sum things up to this point, the conclusion is quite simple.

So, you might think: “Well then, since LEDoS is going to rise, we just need to study it hard, develop it, and sell it.”

But in reality, it’s not that straightforward.

JBD (Jade Bird Display, 极米光电) is a Chinese company that leads the world in the field of ultra-small MicroLED displays. It is virtually the only firm capable of mass-producing the microdisplays essential for smart glasses and AR devices, creating a structure in which global tech giants like Apple and Meta have no choice but to rely on JBD’s supply chain.

Right now, in this market—in this industry—if someone says, “Please supply us with LEDoS, even just samples would be fine,” the only company that can actually deliver is JBD, Jade Bird Display.

If you look at the news, there are plenty of companies saying, “We’re working on LEDoS, we’re doing MicroLED displays,” but most of them are still at the stage of just setting up lines or considering small-scale pilot runs, rather than true mass production.

JBD, on the other hand, is virtually the only company that can actually supply if someone like us says, “We’re going to launch smart glasses, so please provide us with Ledos.”

So right now, as you can see here, most of these companies are allied with JBD, receiving their displays and LEDs from them. Even later, when it comes to mass production, the likelihood is very high that they will all end up working with JBD.

I believe that Apple’s smart glasses currently in development are also highly likely to adopt JBD’s display.

What I am truly concerned about is that it is obvious smart glasses will become the key device in the post-smartphone era, yet Korean companies are not really joining the supply chain.

Korean conglomerates like Samsung and LG, up until the 2010s, were running large businesses in LEDs and filing many patents, but as of now they have effectively withdrawn from the business.

If these two companies had continued operating in this business, they would have responded to MicroLED as well, but the two giant Korean conglomerates today are focusing more on OLEDoS, which can be manufactured by leveraging their existing infrastructure.

Even though LEDoS is technically superior.

I am beginning to think that perhaps in the process of transitioning to LEDoS, Korean display makers might end up losing display hegemony to Taiwan or China.

The only fortunate thing is that there is a Korean company that has a close relationship with JBD.

It is called Sapien Semiconductor, and this company supplies the backplane for the LEDoS provided by JBD.

As confirmed so far, it has been verified that they are supplying smart glass backplanes in alliance with Meta, Sony, and Alibaba.