Why Korea’s Galápagos-ization Became a Blessing in the AI Era

For true sovereign AI, there must be a sovereign internet platform

“You’ve just landed at Incheon International Airport and, after a grueling 12-hour flight, you head to your hotel. Naturally, you open Google Maps, but in Korea it doesn’t work as well as you expect. Pedestrian navigation isn’t supported at all, and routes are displayed incompletely. In the end, you hail a taxi, arrive at the hotel, and ask the staff a question.

‘Why doesn’t Google Maps work well in Korea?’

The staff smiles and replies,

‘People in Korea rarely use Google Maps. We use Korean apps like Naver Map or Kakao Map instead.’”

This phenomenon—where foreign platforms operate only in a limited way compared to the global standard while local platforms grow overwhelmingly—is often called the “Korea Galápagos.” In the past it was even mocked as a symbol of closedness and exclusivity.

For example, Korea’s public institutions and courts still use the domestic word processor Hangul (Hwp) rather than Microsoft Excel.

Messaging is no different. As of February 2025, KakaoTalk holds a staggering 98.9% market share, an almost unheard-of monopoly globally.

In search, Naver still holds a majority. Although it has fallen from the 70–80% range of the past, it remains a rare case of a local service beating global Big Tech.

Today, however, I don’t see this “Korea Galápagos” merely as closedness. I argue that, in the coming AI era—especially in the race for sovereign AI—it can become a secret weapon only Korea possesses.

High-quality “sovereign” data is essential for true sovereign AI

Why are U.S. Big Tech firms so far ahead in developing LLMs?

Capital surely plays a part, but I’d point to the sheer volume of data in English within the total corpus.

Because American internet platforms and services are used worldwide, distributing U.S.-made LLMs globally is that much easier. Interactions with users then further improve those LLMs, creating a virtuous cycle.

However, there are signs this equation is starting to break.

With the Trump administration now in power, a growing number of U.S. allies and countries around the world believe they must not depend on the U.S. for AI, which will have profound implications for security and the economy.

Even so, I believe only a tiny number of countries can actually achieve sovereign AI.

Why? Because sovereign AI requires that a country’s local companies own that country’s data.

If they don’t—if data sovereignty has been ceded overseas—then no matter how much money is poured into building a domestic LLM, its performance will inevitably lag U.S. models. This is why a so-called data barrier is necessary.

In other words, if you want to cultivate sovereign AI now, you must, like the EU, prevent U.S. companies from taking your national data.

Demand stringent personal-information security. Force data centers to be built domestically so data cannot be taken out.

You must. If you don’t have domestic internet companies like Korea or Russia, such tough measures are necessary.

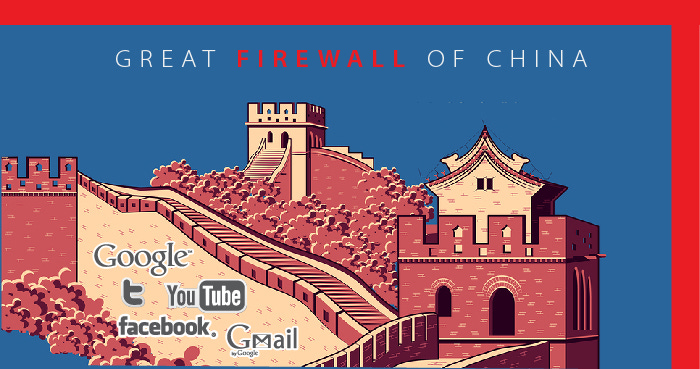

I also believe one reason China is ahead in AI LLMs is that it erected the Great Firewall early, blocking U.S. companies from accessing its national data.

Even if the original intent was to surveil citizens, in retrospect it was the right decision.

Model cases of data sovereignty from Korea

Korea’s digital ecosystem is so unique that, from the outside, it can look almost aberrant. Local monopoly platforms—not global standards—dominate nearly every aspect of daily life.

First, there’s the messenger KakaoTalk. In Korea, it’s no exaggeration to say that essentially 100% of smartphone users are on KakaoTalk. The 98.9% share as of 2025 isn’t just a number; it means people’s conversations, photos, payments, group activities, and shopping—digital records of everyday life—are all piling up within one platform. In other words, vast data on the language, culture, and behavior patterns of Korean society is aggregated in a single channel called Kakao.

Second, there’s the portal and search engine Naver. Google dominates globally, but in Korea Naver still holds a majority. Users search news, post on blogs, and ask questions on Knowledge iN. This data is not just search logs; it functions as a unique qualitative dataset reflecting the concerns, interests, and daily context of Koreans. It’s an asset on a wholly different plane from English-language data.

Third, there is local office software such as Hangul (Hwp). Public agencies, courts, and schools still use this word processor as a standard, shaping the form of administrative and legal documents and research materials. This too enables a level of data independence you don’t see elsewhere. The administrative and legal language data of Korea is preserved within the domestic ecosystem rather than flowing to overseas platforms—hugely significant.

In short, Korea is an unintended case of securing “data sovereignty.” Global Big Tech failed to put down roots, and instead, the language and life patterns of the people have been systematically accumulated inside local platforms. This data pool is not only the foundation for training Korean-language LLMs but also the core resource needed to build true sovereign AI that reflects the sociocultural context of Koreans.

Let’s now address the export of Korea’s map data to the United States, which I mentioned in passing above.

Since first applying to the Korean government in 2007 to export map data, Google has continuously pushed to take Korean map data to the U.S.

What Google wants is a fixed-scale “1:5,000” high-precision map. At that precision, 1 cm on the map corresponds to 50 m in the real world, allowing detailed representation of alleyways and buildings. It’s five times more precise than the 1:25,000 maps Google currently uses.

Interestingly, Google applied for this on February 18 of this year—less than a month after the start of the Trump administration’s second term.

The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) has labeled Korea’s restrictions on map exports a “non-tariff barrier” and is exerting pressure.

Back in 2011 and 2016, applications were blocked largely on security grounds. This time, however, the U.S. government itself is applying direct trade pressure.

Why are Google and the U.S. government so eager for Korea’s map data?

Because exporting this data doesn’t just mean making Google Maps more convenient.

This map data can be used indefinitely. In the AI era, it’s akin to digital crude oil.

For example, a 1:5,000 ultra-precise map includes detailed information such as lanes, road boundaries, and signs—data essential for training autonomous-driving AI. In other words, Waymo could use it to gain competitiveness in autonomous driving within Korea.

That would mean Korea serves merely as a testbed for future mobility while core technologies and platforms remain dependent on the U.S.

Even the autonomous-driving technologies developed by Korea’s Hyundai or Naver could lose competitiveness within Korea itself.

Moreover, future services—delivery robots, drones, AR navigation—will all operate on fine-grained spatial data. The company that holds data down to Korea’s narrow back alleys will preempt the related service-robot and AR markets.

Therefore, exporting Korea’s map data overseas effectively hands over the very foundation of future industries to other countries. Korea is trying to stop this.

The future of a Korea-style sovereign AI

I don’t think any country other than the U.S. and China can catch up with ChatGPT/DeepSeek.

The Middle East? There’s plenty of money to buy lots of GPUs, but there are far too few developers and researchers.

Korea? It’s fairly capable in AI hardware, but it is very short on both GPUs and research talent.

That’s why I believe Korea should move toward industry-specialized AI.

Take healthcare, for example.

In reality, medical techniques and treatment methods are about 85% the same across countries.

The differences lie in the remaining 15%.

That 15% diverges by country due to differences in body type, weight, diet, and so on.

So let’s say the global commonality covers that 85%.

The real contest is in the remaining 15%.

You have to train and deliver that 15% differently, country by country.

I’d like to call this the 85% rule.

I believe this will become Korea’s export model for sovereign AI.

Thinking more broadly, sovereign AI competitiveness will be determined by that remaining 15% of local data and context.

As I said above, securing that 15% of data is ultimately what matters most.

But at this point, it’s unrealistic to build local internet platforms to take on U.S. Big Tech.

Therefore, let me again offer the policy approach I proposed above.

Even now, follow the EU’s approach.

Block U.S. Big Tech from acquiring your local data.

Demand strict information security so your data remains within your country.

That is the only way to achieve sovereign AI.

In closing…

Although Korea’s Galápagos-ization has been mocked, I believe it has become a powerful moat in today’s AI era.

Now, if anyone wants to do something AI-related in Korea, they must partner with Korean companies to secure data.

For the same reason, I believe Russia also has the potential to achieve sovereign AI.

Russia, too, has a significant number of local internet platforms and thus meets many prerequisites.

Of course, U.S. sanctions blocking imports of NVIDIA GPUs are a major bottleneck.