Why did the memory chicken game keep repeating—and who ultimately survived?

Micron’s history is the history of the memory chicken game.

I originally planned to write about Micron’s history.

But if the goal is to forecast the future from the past, it’s more accurate to dissect the memory industry’s chicken-game mechanics than to trace a single company’s timeline.

This piece isn’t about who wins, but what it takes to win.

As my final post of the year, I want to start with the most important question.

Will there be another chicken game in the future?

I can’t say “no” with absolute certainty, but I want to argue that the probability is extremely low.

In the classic sense of a memory chicken game—one that ends with a major incumbent exiting—there are hardly any targets left.

Even if Samsung wanted to wage another memory “chicken game,” the field has narrowed to just three players, so shrinking the player set any further is close to impossible.

In particular, the moment there are any signs of an attempt to start a chicken game, regulators around the world will be watching closely due to antitrust concerns.

Semiconductors as strategic assets

Semiconductors have become a strategic industry watched closely by governments worldwide, so this is no longer a market where companies can invest and compete entirely on their own.

In particular, Samsung driving SK hynix into bankruptcy would not be tolerated by the Korean government—and it’s unclear whether it would even be possible.

And if Samsung tried to go after Micron, it would almost certainly invite retaliation from the U.S. government.

The remaining possibility—however slim

Still, there is a fingernail-sized chance that a chicken game could return—this time against Chinese memory semiconductor companies.

That said, it’s hard to argue this is likely. Chinese memory makers are the product of massive state backing, with tens of billions of dollars in subsidies and the full weight of the Chinese government behind them. Could Samsung win a power struggle against the Chinese government? I don’t think so.

Alright—before we dive into the history in earnest, let me first explain what it takes to survive a memory chicken game.

Survival Rule #1: Get bigger

For example:

If you spend $100 million to build a fab and produce 100 million chips, the cost per chip is $1.

If you produce 200 million chips? It becomes $0.50.

In other words, the moment you cut production, the cost per chip spikes.

In the end, to survive in an industry like this, you have to push utilization to the absolute limit and drive costs down as much as possible.

And this is exactly when Samsung makes an extremely bold move.

In the late 1990s, when DRAM prices collapsed, most companies hunkered down and argued that they should cut output—but Samsung Electronics moved in the opposite direction. As a chaebol, Samsung could pull cash from other affiliates and held massive liquidity, so during the downturn it aggressively increased capex and even raised its production targets—an unusually decisive stance.

Samsung, which had already become the world’s No. 1 memory maker in 1993, understood that if it expanded output further, it would gain an overwhelming advantage over its competitors.

Survival Rule #2: Spend like crazy on R&D

In the DRAM industry, shrinking the process node—reducing the nanometer width—to survive leads to an increase in supply, as it allows for a higher net die per wafer. (This is largely a narrative of the past, as the logic has become less applicable in today’s 10nm-class era.)

This, in turn, triggers a vicious cycle that exerts downward pressure on prices. Conversely, companies that fail to scale their processes produce lower volumes, which translates to a higher burden of fixed cost absorption.

Survival Rule #3: Hold an enormous cash war chest

People often describe the memory semiconductor business as one where you make a ton of money during upcycles—and then give a ton of it back during downcycles.

The problem is that if you don’t have enough cash to survive the downturn, the company goes bankrupt. On the other hand, if you have an enormous cash war chest, a downturn becomes the moment you’re holding the knife that can cut down your competitors.

Samsung, as a chaebol, could pull massive funding from its financial affiliates. I think a big reason Samsung has been able to defend its memory throne to this day is precisely because it’s a chaebol.

The introduction ran a bit long. Now, let’s get into the main body.

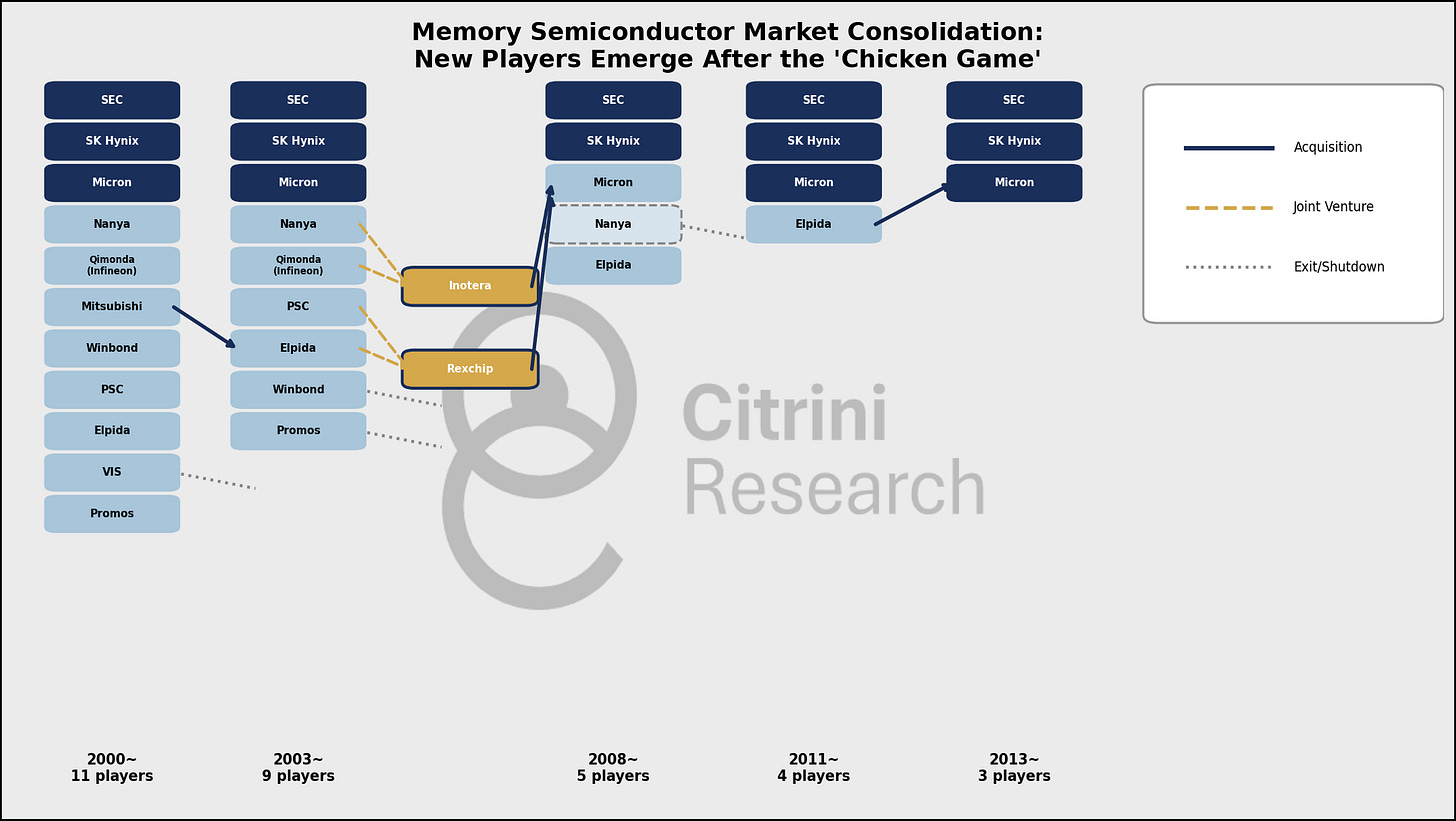

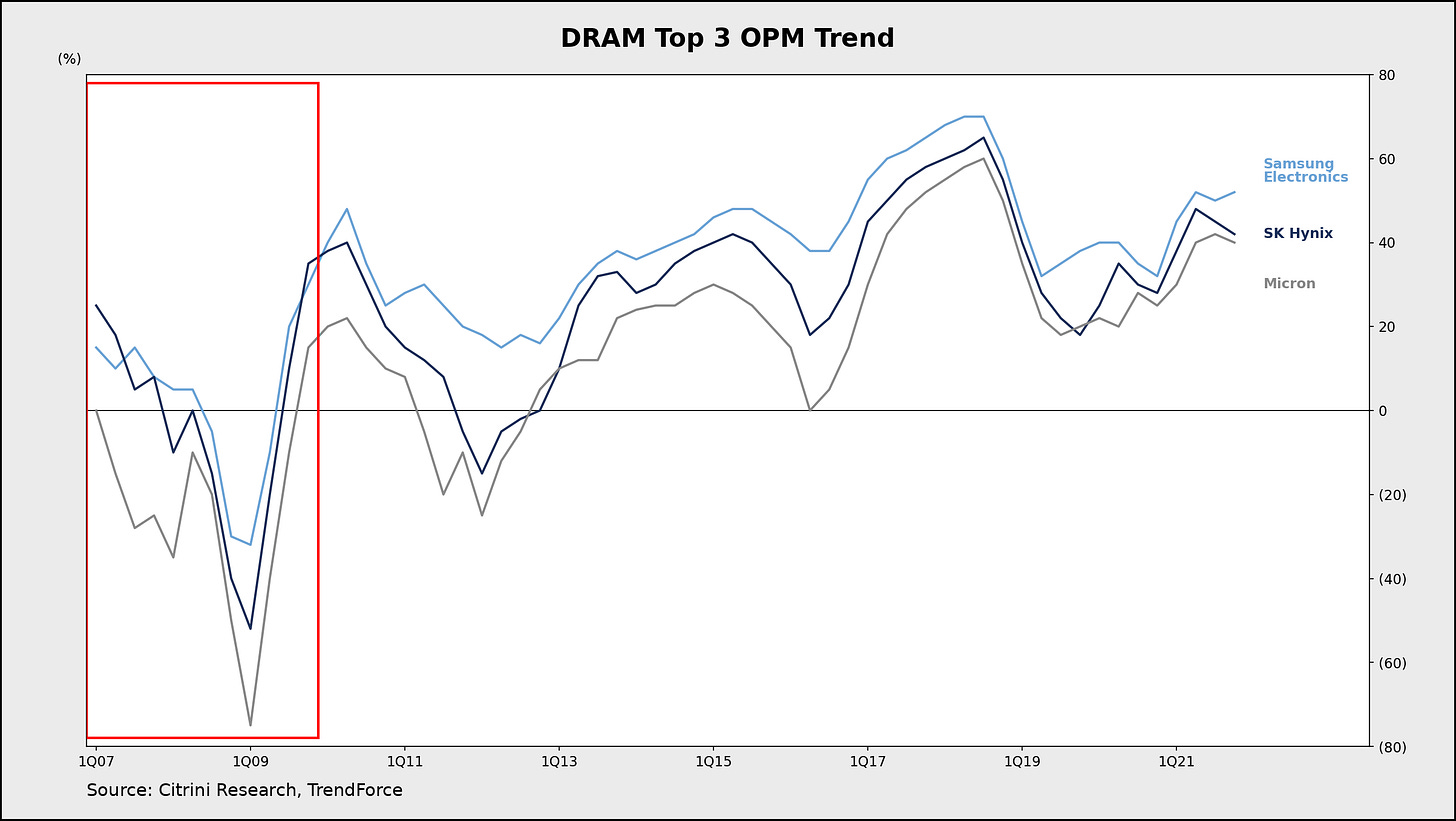

From 2007, Taiwanese companies began aggressively expanding supply, which triggered the first “chicken game.” Starting in 2008, this overlapped with the severe demand slump caused by the U.S. financial crisis, and DRAM prices collapsed from $6.8 three years earlier to $0.5.

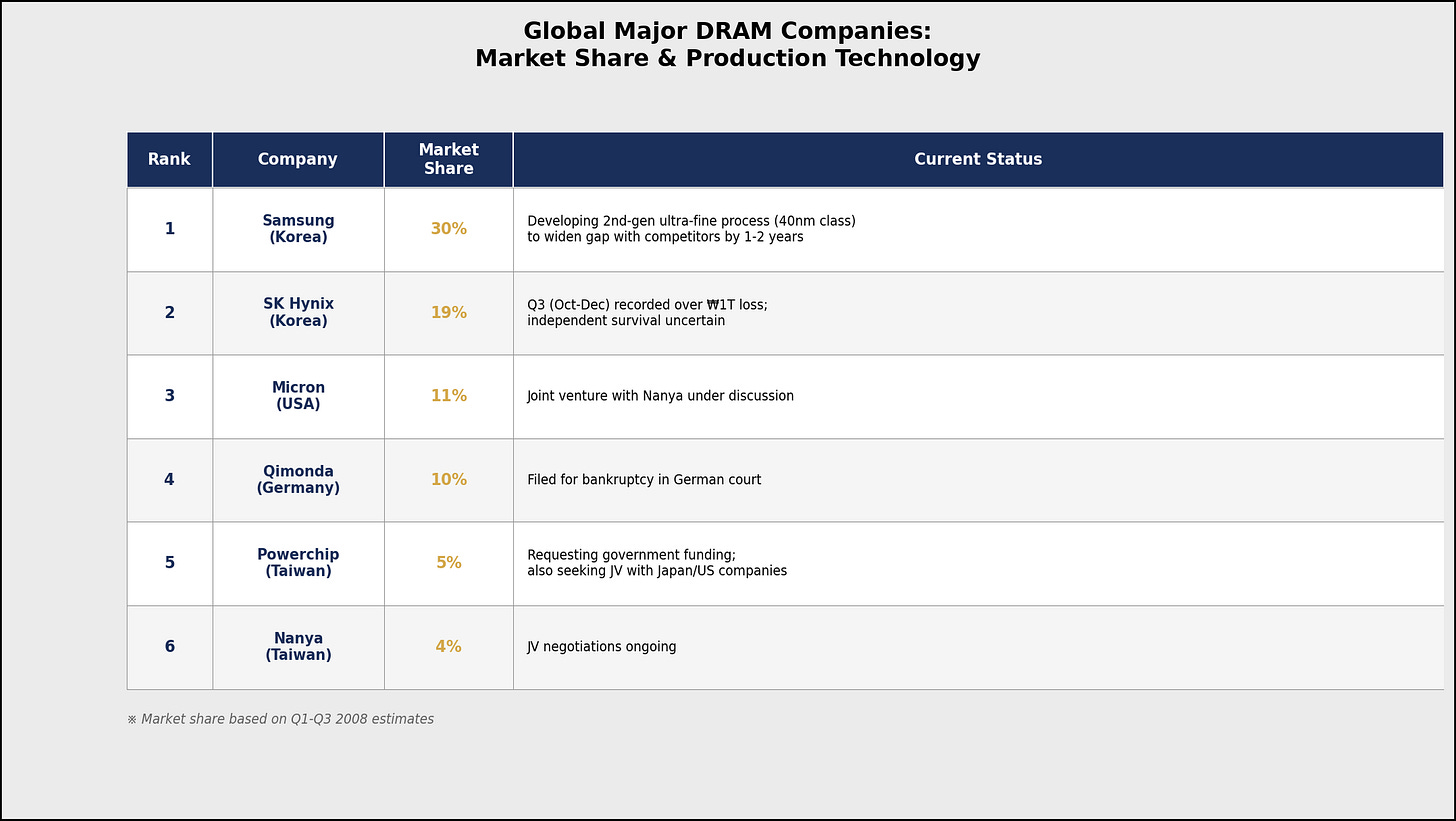

At the time, there were around 10 companies in the market. Market share was roughly Samsung Electronics 30%, Hynix 19%, Japan’s Elpida 15%, U.S. Micron 11%, Germany’s Qimonda 10%, Taiwan’s Powerchip 5%, and Taiwan’s Nanya 4%.

The chicken game that began in 2007 was, surprisingly, initiated first by Taiwanese companies.

It may feel quite surprising that smaller Taiwanese players struck first, but in fact, they had their own rational outlook.

It was the alliance.

Back then, Taiwanese firms lacked independent technological capabilities. Instead, they pursued a coalition strategy: [Japanese/German technology + Taiwanese manufacturing capacity].

Structure:

Technology providers: Elpida (Japan) and Qimonda (Germany) provide leading-edge process technology.

Manufacturing: Taiwanese companies such as Nanya, Inotera, Powerchip, and ProMOS keep the fabs running.

This is how they calculated it: “Samsung is alone, but we are united. If we combine Japan and Germany’s technological edge with our low-cost manufacturing, we can encircle Samsung with volume and bleed it dry.”

But reality was ruthless. When the crisis hit, the “alliance” crumbled like sand. As the technology providers (Elpida and Qimonda) began to falter, the Taiwanese fabs that depended on them saw process upgrades come to a halt. Meanwhile, Samsung—an IDM (integrated device manufacturer)—was able to move fast, with rapid decision-making.

Beyond this, Taiwan made two major misjudgments.

First, the Taiwanese government’s “Two Trillion Twin Star” policy.

I think this may have been the biggest reason. At the time, the Taiwanese government pushed the “Two Trillion Twin Star” project, aiming to grow semiconductors (DRAM) and displays (LCD) as the nation’s two core pillars.

The government’s money line: the Taiwanese government poured massive subsidies, tax benefits, and low-interest loans into DRAM makers.

Taiwanese companies thought like this: “Even if we run losses, the government has our back, so we won’t die. If we flood the market and drive prices down, firms in other countries without government support will die first.”

But, unfortunately, as we all know, industries that receive government subsidies usually do not end well. Instead of building self-sustaining competitiveness, they only grew in size, and when the financial crisis hit, losses piled up to a level that even the Taiwanese government could not bear. In the end, Taiwan’s DRAM industry was left as nothing but an empty shell.

Also, they failed badly in their market forecasting.

Microsoft’s “Windows Vista,” released in 2007, was expected to be the savior of the PC industry.

Memory makers imagined it like this: “Vista is going to consume an enormous amount of memory. If PCs around the world upgrade to Vista, DRAM demand will explode. We need to expand our fabs now so we can rake in money.”

But as always, MSFT is terrible at operating systems. Vista turned out to be the worst OS. It was heavy and full of bugs, so consumers turned away. Demand didn’t rise, yet DRAM kept pouring out of the Taiwanese fabs they had expanded. Oversupply + the financial crisis = a massive price collapse—the worst-case scenario brought to life.

Even Samsung Electronics posted massive losses at the worst point of the cycle (4Q08–1Q09), with an operating margin around -30%. For the other players, survival was uncertain without government support—let alone the ability to keep investing in technology.

3Q08: Samsung Electronics was the only company to remain profitable with $200 million in operating profit, while Hynix -$400 million (OPM -28%), Micron -$450 million (OPM -35%), Powerchip -$530 million (OPM -100%), and Nanya -$300 million (OPM -69%) all posted losses.

4Q08: Samsung Electronics recorded -$900 million (OPM -14%), Elpida -$930 million (OPM ??), and Nanya OPM -105%.

Ultimately, Qimonda—then the No. 5 player with roughly 10% market share—filed for bankruptcy in January 2009. Its cumulative losses from 3Q07 to 4Q08 exceeded $3 billion, and despite receiving $500 million in support from the German government, it still ended up going bankrupt.

Japan’s Elpida also came close to collapse due to massive losses, but managed to barely survive after receiving $240 million in Japanese government support and $90 million in creditor support in February 2009.

Smaller Taiwanese players suffered even more severe losses relative to their size, but they managed to hang on thanks to KRW 2.8 trillion in Taiwanese government support and backing from their parent companies.

Hynix held up relatively well at the time because it ranked #2 in both market share and technological capabilities. However, the scale of its losses was so large that there were talks about selling the company to another conglomerate or even to Micron. Its stock price collapsed from around KRW 40,000 to the KRW 5,000 range—an eightfold drop.

With a massive operating loss (OPM -53%), its BPS was cut in half, and its PBR fell from about 2x to 0.5x. But after surviving the first chicken game and the global financial crisis, Hynix fully recovered its share price during the upturn that followed.

After the first chicken game, as the economy recovered, the DRAM industry briefly entered a boom period.

However, in 2010, aggressive investment ramp-ups in Japan triggered a second chicken game. DRAM prices quickly fell from $3 to $1 (based on DDR3 1Gb).

A notable point is that this chicken game started with Japanese companies first.

As with the first chicken game, it wasn’t the #1 or #2 players that kicked it off—what’s worth paying attention to is that a relatively smaller player made the first move.

Of course, the Japanese firms had their own reasons for doing so.

There are three main reasons.

They tried to break through the “curse of a strong yen (Endaka)” with volume.

The most fundamental cause was the exchange rate. At the time, the yen surged to an all-time high (USD/JPY in the 70–80 range).

Back then, Korean players (Samsung, Hynix) could still make a profit even selling a single chip thanks to a weak won, but Elpida was structurally in the red even if it did nothing, because of the strong yen.

So Elpida began to think: “Because of FX, the loss per chip is huge. Then we need to increase production volume (Q) to an extreme degree and sharply lower the fixed cost per chip (depreciation). That’s the only way we can match Samsung’s pricing.”

Following that logic, they forced their fabs to run at full capacity and flooded the market with supply—but this ended up triggering global oversupply and ultimately backfired on them.

The second reason is, once again, similar to the case of the Taiwanese companies.

Namely, the massive amount of public funds poured into Elpida.

Right after the 2009 global financial crisis, the Japanese government injected 30 billion yen in public funds and 100 billion yen in loans into Elpida in order to save its pride—the semiconductor industry.

Once it had taken government money, Elpida’s management had to quickly show “visible results (market share expansion, a technological leap)”. There was political and managerial pressure that left them no choice but to invest aggressively rather than stay defensive.

The critical misjudgment was that instead of concentrating this funding on technology R&D to strengthen the fundamentals, they poured it into expanding capacity (Capa, production capability) to protect their near-term market share. In the end, it was as if they simply used Japanese taxpayers’ money to fatten the wallets of semiconductor equipment companies.

The third reason was the shift toward mobile DRAM.

Seeing the smartphone market opening up at the time, Elpida tried to restructure itself from PC DRAM toward mobile DRAM.

The strategy was: “PC DRAM is a red ocean. Let’s increase the share of mobile DRAM (supplying iPhones, etc.), which we do well.” The intention was good. Even looking back now, it was truly forward-looking. The problem, however, was yield.

As the process transition to mobile DRAM progressed more slowly than expected, a flood of defective or off-grade products came out, and by dumping them into the PC spot market at rock-bottom prices, they further fueled the plunge in DRAM prices.

In the end, Elpida judged that if it stayed still, it would inevitably die—crushed by the strong yen and a lack of cost competitiveness—so it borrowed government money and placed a gamble to win through “economies of scale.”

But Samsung Electronics had already stabilized its 40nm-class advanced process by this time and pushed its costs even lower, and it comfortably absorbed Elpida’s volume offensive (a counter-fire strategy), ultimately driving Elpida into bankruptcy (2012).

Ironically, Micron ended up reaping the greatest rewards from the memory “chicken game.”

When you interview Micron engineers, there’s a line you hear again and again:

“The whole company is obsessed with efficiency.”

Let me explain in more detail.

Inside Micron, an extreme cost-cutting culture—born out of crisis—has taken deep root across the organization. For example, they simplified manufacturing processes as much as possible, minimized die size to pack more chips onto each silicon wafer, and pushed every other step of the flow to run faster and process higher volume with maximum efficiency.

And they had one more hidden card: Micron’s headquarters wasn’t in Silicon Valley—it was in Idaho. That meant lower employee churn, and dramatically cheaper land and electricity.

All of these factors combined allowed Micron, especially in its early days, to compete head-on on price with Japanese memory semiconductor companies.

In the late 1990s, when an extremely severe downturn hit the entire memory market, Samsung waged a chicken game, and the market ended up flooded with DRAM. Prices collapsed due to massive oversupply, and because of Samsung, the oversupply period dragged on far longer. On top of that, every company was in a situation where even if they sold chips, they were barely breaking even—or taking losses. Because of the chicken game Samsung Electronics ignited back then, countless semiconductor companies fell into financial distress.

But interestingly, Micron’s playbook was completely different from Samsung’s. Instead of fighting an all-out war like Samsung, Micron chose a strategy of buying companies that had fallen into financial trouble. In other words, they decided to use the moment to increase their weight class. First, in 1998, when Texas Instruments gave up its memory business, Micron acquired all of TI’s memory fabs and instantly grew into a core player in the memory industry. Then in 2002, Micron even attempted to acquire Hynix in Korea. That deal fell through because Hynix rejected it, but if the acquisition had succeeded, it was almost certain Micron would have surpassed Samsung in scale and taken the No. 1 market share position at the time.

Micron continued to push the same playbook afterward. As the Taiwan-driven memory chicken game pushed the industry into crisis, Germany’s Qimonda fell into a liquidity crunch in 2008—and Micron moved quickly, snapping up Qimonda’s 35.5% stake in Taiwan’s Inotera. Likewise, in 2012, Micron acquired Japan’s Elpida after it went bankrupt. You could call this a true masterstroke. The total acquisition price was 200 billion yen, but the actual cash Micron paid was only 60 billion yen. The remaining 140 billion yen was on an interest-free installment basis—so it was close to a conditional, almost-free acquisition. And at the time, Micron was strong in PC DRAM, but it lacked mobile DRAM capabilities. But who was Elpida? A major supplier of mobile DRAM to Apple. So that acquisition meant Micron caught two huge rabbits at once: it entered the mobile DRAM market overnight, and at the same time it moved into Apple’s supply chain.

Micron didn’t stop there. In 2016, it acquired the remaining stake in Inotera and turned it into a fully owned 100% subsidiary. So what happened then? First, by fully integrating Taiwan’s process operations into Micron’s global R&D network, it could maximize manufacturing efficiency. It also secured collaboration routes into Taiwan’s semiconductor ecosystem. In other words, rather than Samsung’s push-forward expansion, Micron pursued a fairly conservative expansion strategy—placing precise bets when opportunities appeared. And as this strategy worked, Micron’s weight class kept growing, and it ultimately became part of the memory Big 3 alongside Samsung and Hynix.

Micron’s conservative DNA also showed up very clearly when ASML’s EUV lithography tools emerged. In the late 2010s, semiconductor scaling became far more complex than ever before, and ASML’s tools were essentially monopolizing the world’s fists. The problem was that EUV tools were unimaginably expensive, and because it was a new technology, early yields were low and it took quite a long time to stabilize the process. At that time, Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix boldly adopted EUV, but Micron instead delayed adoption. They chose to push existing technologies to the absolute limit in order to lower the cost structure. This directly connects to Micron’s inherent character. From its earliest days, this company has been almost obsessive about cost reduction and extreme efficiency, and that conservative investment discipline has continued all the way to today.

The Survivor’s Peace: Why the War is Likely Over

In the end, what was the result of the blood-soaked memory chicken game that lasted for decades? The Warring States era—when dozens of players ran rampant—is over, and the world has now been divided into a “Big 3”: Samsung, SK hynix, and Micron.

What’s interesting is that each of these three survivors endured in a completely different way.

Samsung: Survived by crushing opponents with overwhelming capital strength and preemptive capacity investment (The Conqueror)

SK hynix: Survived by holding on to the very end through bone-grinding technological development, even while facing a life-or-death crisis under creditor control (The Fighter)

Micron: Survived by growing its size through ruthless efficiency and an M&A strategy of absorbing fallen enemies (The Hunter)

The market that these three companies—each with different DNA—have created by surviving is completely different from the past. When there were ten players, even if I cut output, someone else could simply increase theirs. But now that only three remain, everyone knows all too well that if anyone recklessly expands supply, everyone goes down together.

In other words, the market paradigm has shifted from a “market share (M/S) war” to “profit maximization.” This is the strongest structural basis for my argument that “the probability of another large-scale chicken game happening again in the future is extremely low.”

And there’s a particular anecdote I want to share.

1978, the year Micron was born, was the worst possible timing to start a semiconductor business.

This was the era when Japanese companies were flooding the market with cheaper and better DRAM, pulling ahead of American firms across the board. It was a time when most U.S. semiconductor companies were bleeding heavily year after year.

Back then, Micron’s founders, Joe Parkinson and Ward Parkinson, didn’t go looking for Silicon Valley billionaires—they went to Jack Simplot, the richest man in Idaho, nicknamed the “Potato King.”

Jack Simplot didn’t know much about technology, but he grasped one fundamental truth that cuts through the memory industry.

“Memory is a commodity.”

He saw through the situation: with Japanese companies pouring DRAM into the market, prices would crash to the floor. Having spent his entire life dealing with potatoes, he knew exactly what that meant—this was the bottom of the market, the moment when prices would fall as far as they could and competitors would collapse, and therefore the right time to enter.

So he boldly invested millions of dollars into the Parkinson brothers—and succeeded in multiplying it by tens, even hundreds of times.

However, I want to argue that this “memory is a commodity” truth is gradually breaking down.

The birth of HBM is a perfect example.

HBM, for now, is still a product you can manufacture and pile up as inventory.

But we’re entering an era where customization is added to the base die, foundry nodes are used, and the specs demanded by each customer diverge.

From that point on, HBM from DRAM manufacturers starts to resemble a foundry business.

The expansion of cHBM (custom HBM) is inevitable, and this will ultimately spread the effect of signing LTAs across the DRAM industry.

Right now, DRAM prices are exploding, and HBM prices are being raised accordingly. Later on, even if commodity DRAM rides a cycle and prices rise, it will become difficult to raise HBM prices in the same way—but in exchange, you gain guaranteed sales.

Both an escape from the commoditization of memory, and the “foundry-ization” of memory, will happen. Within the next two years.

Some people also point out that even an LTA can be terminated mid-stream.

If that happens, then we simply cut cHBM output. Just like TSMC reduces wafer starts when iPhones sell less.

Of course, I’m not claiming that the cycle of the entire DRAM market will disappear. I just want to argue that going forward, it will inevitably be less affected by the cycle.

Shouldn’t we stop valuing memory companies by P/B now?