TrendForce Roadshow Korea Review

2026 HBM Outlook/ China's 5nm/ Foundry Mature Node Oversupply

The TrendForce roadshow was held a few days ago, and it covered the following four topics.

Outlook for the Display Industry

Outlook for Humanoid Robotics

Current Status and Outlook of the Memory Semiconductor Market

Foundry Market Outlook, including a Perspective on Mature Node Foundries

Among these, the display section and humanoid section will be summarized briefly. Instead, the memory semiconductor and foundry market sections will include detailed explanations along with attached images.

MacBook Pro OLED is scheduled for release in Q2 2026.

MacBook Air OLED has been delayed to 2029.

MacBook Pro will adopt tandem OLED.

Mass production of MacBook Pro OLED panels is planned for Q2 2026.

Due to aggressive capacity expansion by Chinese display manufacturers, there is a risk of oversupply in OLED notebook panels.

There was also mention of Meta’s OLEDoS-based XR device, Meta Project Puffin:

110g

0.9-inch OLEDoS

FOV < 90° (TBD)

Regarding humanoids, much of the content was quite abstract and speculative.

One particularly interesting point was that the Tesla Optimus 3rd generation has been delayed to early 2026. The reason is that the robot hand of the 3rd generation Optimus currently has a lifespan of only about six weeks, which is far from meeting commercial requirements.

And now, we will move on to the memory semiconductor section.

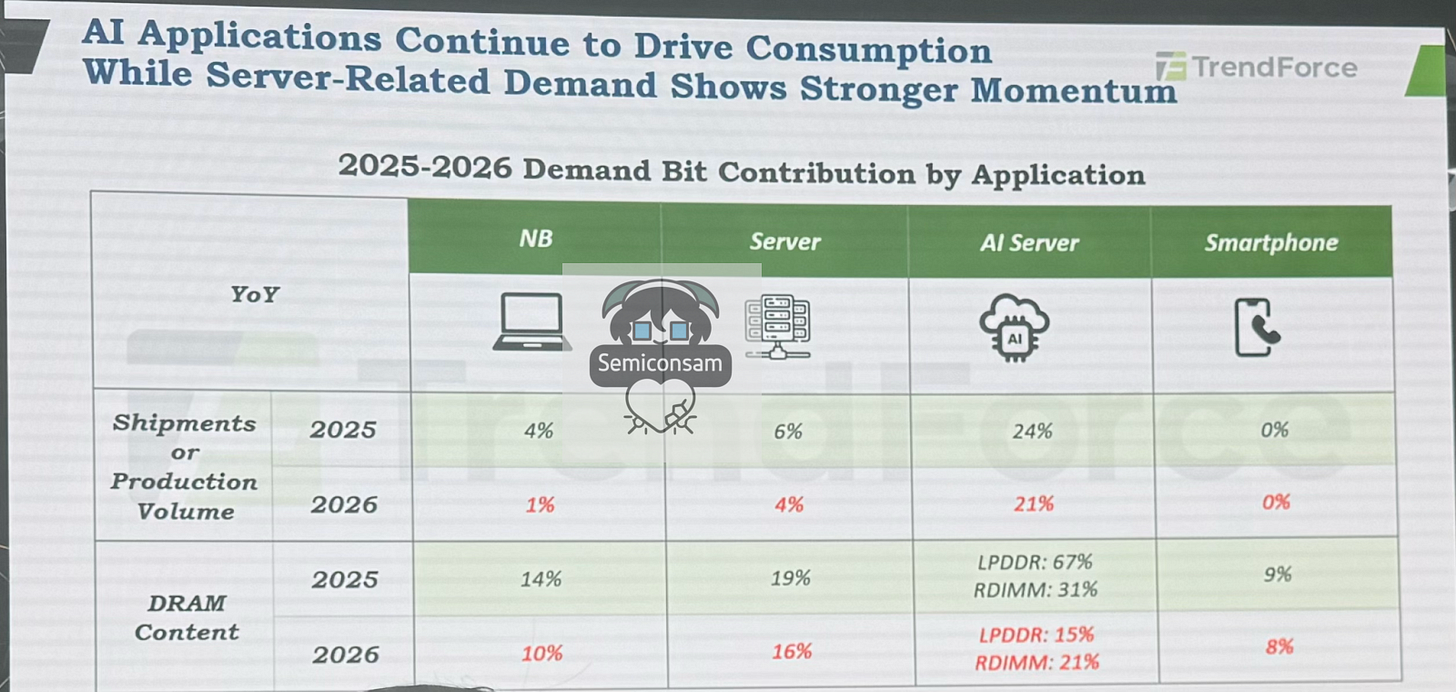

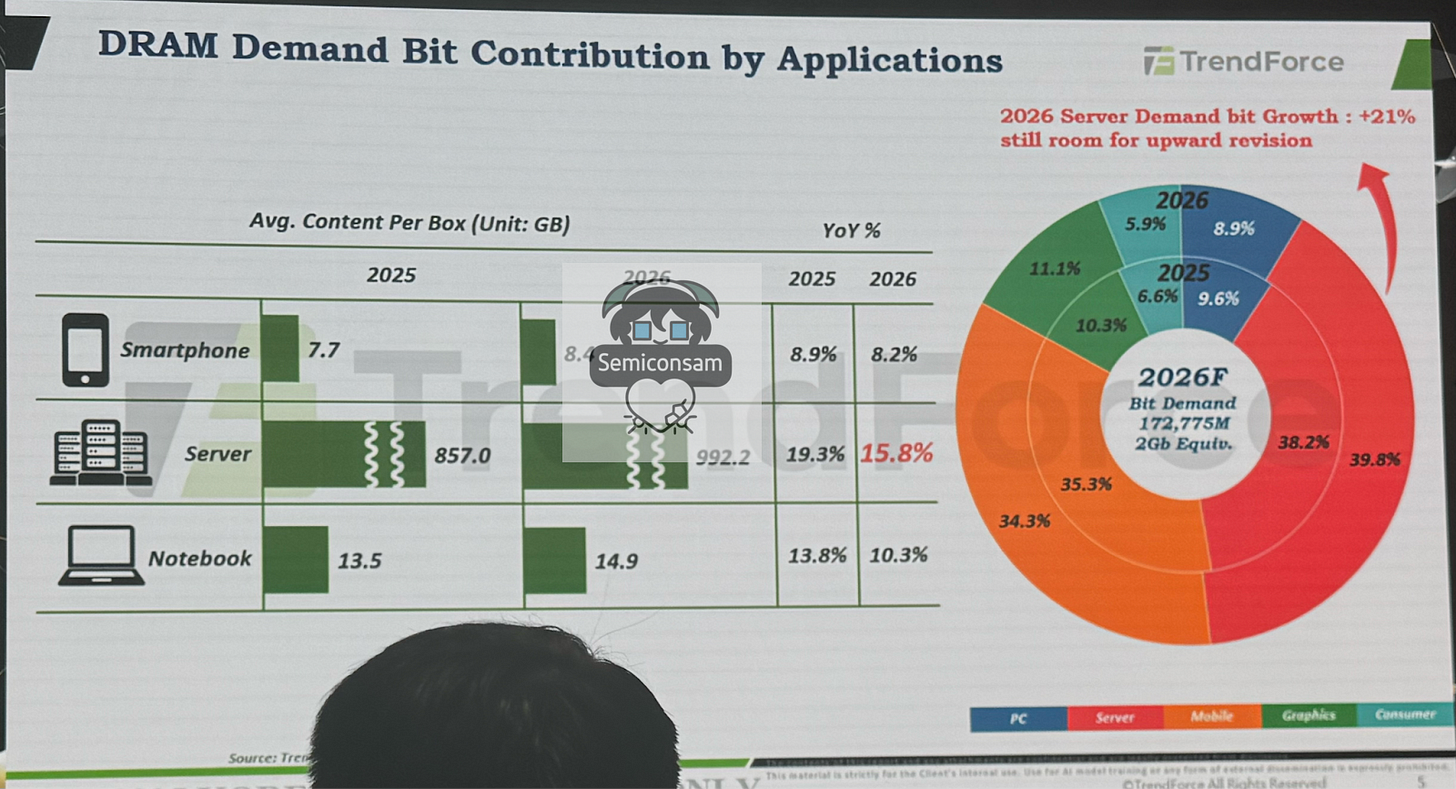

The growth of the DRAM market in 2026 is essentially driven by AI servers and general-purpose servers. In particular, the recovery in general-purpose servers is expected to make a meaningful contribution to DRAM demand. Also, while PC shipments are relatively modest, the notable increase in DRAM content per device deserves attention (driven by AI PCs).

Server DRAM capacity per box has effectively entered a phase of rapid acceleration.

We are now seeing a 15% increase in memory content per server.

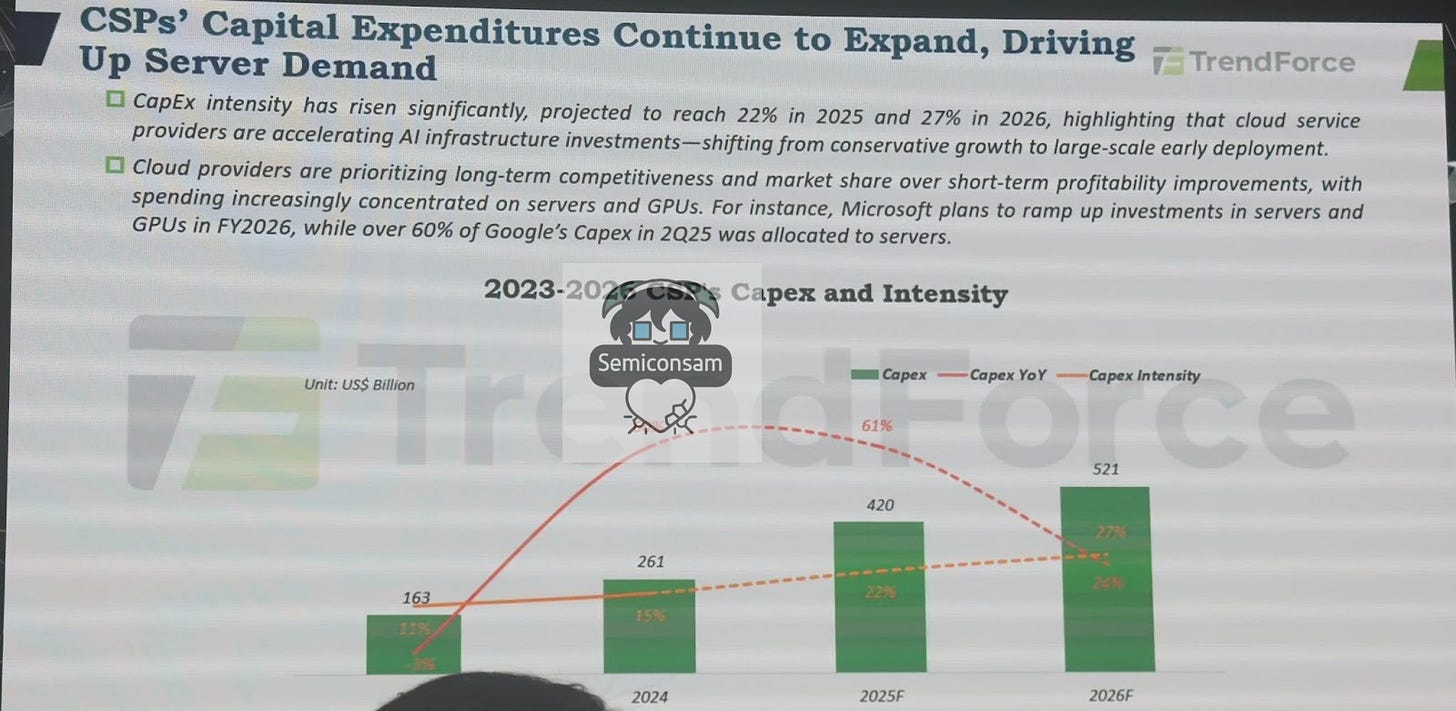

The direction of investment is clearly shifting toward servers and GPUs.

CapEx intensity (CapEx as a percentage of revenue) is projected to rise to 22% in 2025 and 27% in 2026.

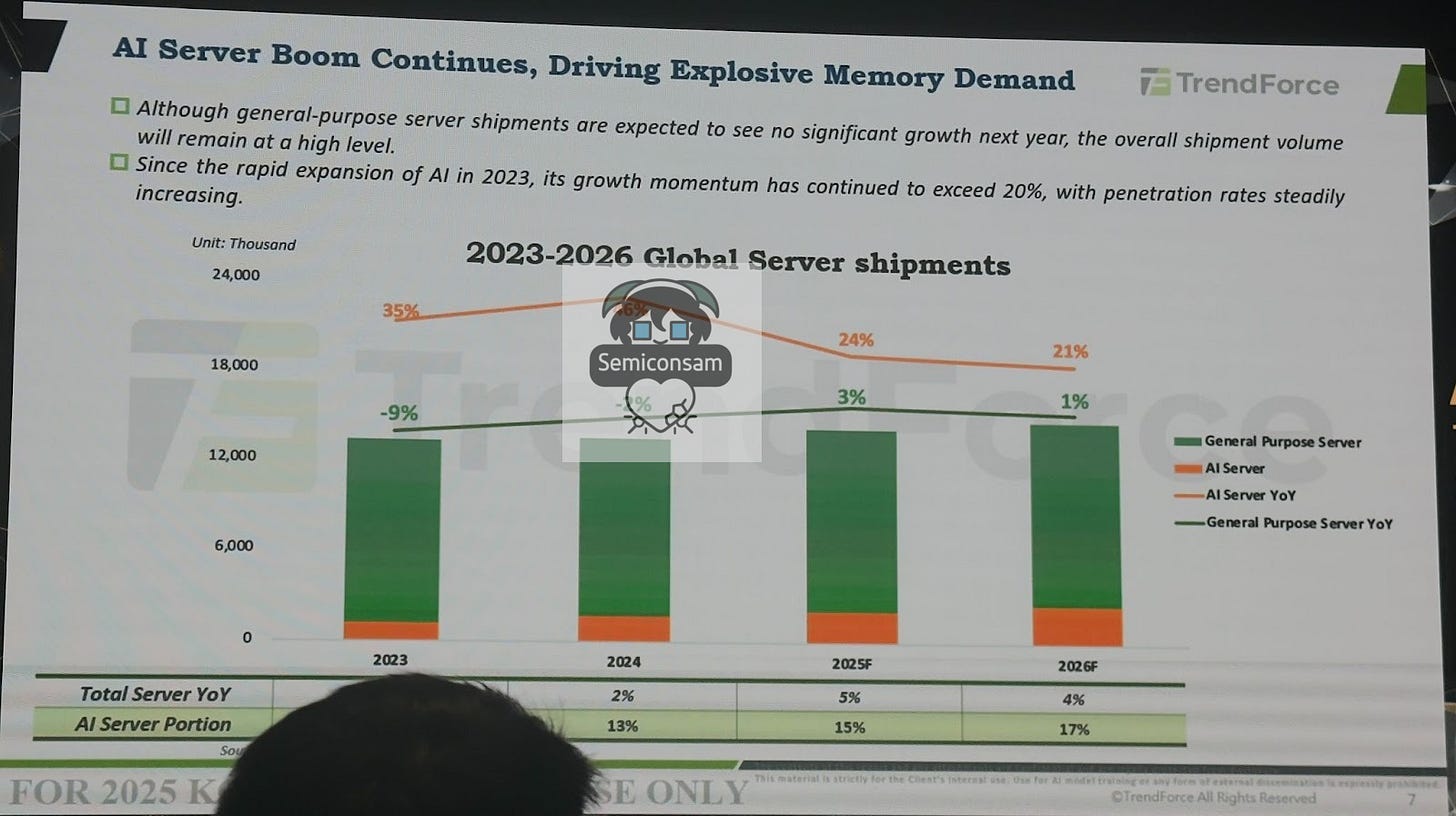

The shipment volume of general-purpose servers is expected to grow by only around 1%, which essentially indicates a state of stagnation.

I share a similar view.

When AWS began placing large orders for general-purpose server DRAM earlier this year, many interpreted it as the beginning of a long-awaited replacement cycle for general-purpose servers. However, my view has been that CSPs simply do not have the bandwidth to refresh their general-purpose fleets right now. And even if they wanted to, the recent surge in memory prices may make such upgrades unfeasible in practice.

(It’s worth noting that in general-purpose servers, DRAM accounts for nearly 10 times the share of total BoM cost compared to AI servers.)

AI server share is increasing from 13% → 17% → approaching 20%, indicating that the proportion of AI servers within the overall server market is steadily expanding each year.

As much as the market is benefiting from AI server demand, it’s also fair to say that dependence on AI servers is increasing as well.

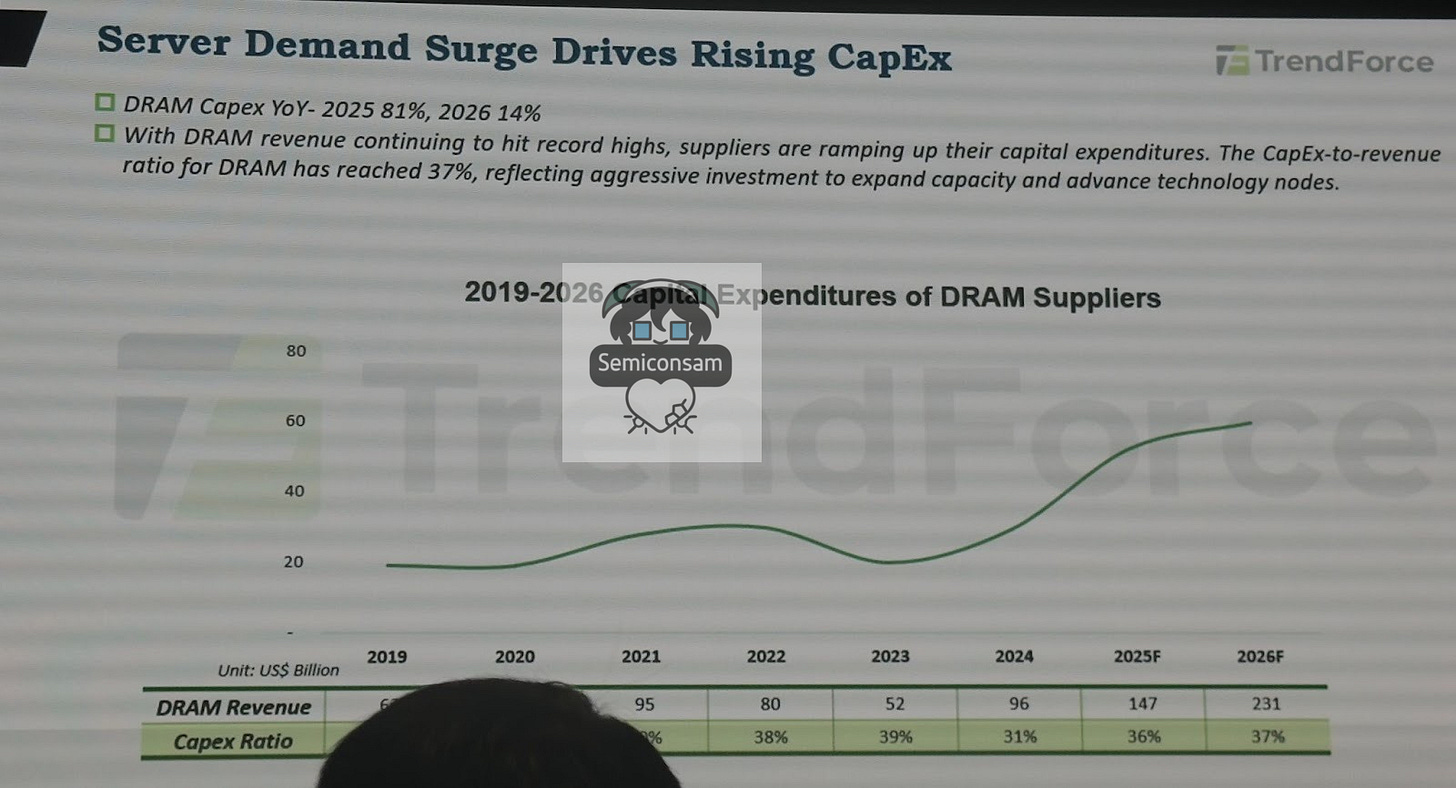

The DRAM CapEx increase of +81% in 2025 and +14% in 2026 may appear lower than one might expect.

However, this is essentially unavoidable.

Even if equipment is ordered now, most suppliers (except Samsung) currently lack available cleanroom space to install it. In other words, they must wait for new fab construction or expansion to be completed before any meaningful ramp-up can occur.

This means that for the two DRAM suppliers other than Samsung, it will take at least another 10 months for CapEx spending to translate into actual capacity expansion.

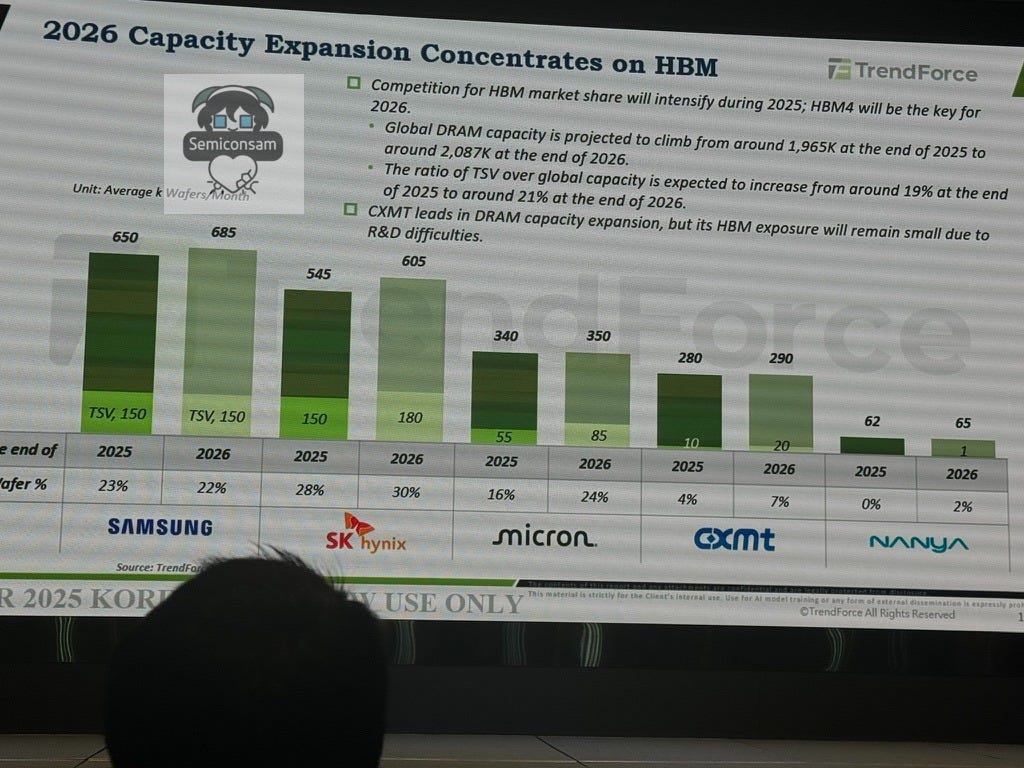

TrendForce interprets this as Samsung not aggressively increasing its HBM allocation.

In other words, Samsung is signaling that it may continue to allocate part of its capacity to general-purpose DRAM rather than pouring capacity into HBM.

Instead of expanding new fabs for HBM, Samsung appears to be prioritizing maintaining existing production levels and focusing its CAPEX on process efficiency improvements.

Also, SK hynix’s massive capacity expansion stands out (an increase of about 60K wafers per month).

The additional 30K increase in TSV capacity suggests that SK hynix is entering the HBM4 phase with a considerable level of confidence.

Micron’s capacity increase is extremely limited.

It is likely to remain minimal until the Singapore and New York fabs come fully online.

I will also comment on CXMT.

While the company produces a large volume of DRAM, it remains significantly behind in HBM R&D, indicating that its ability to compete in the HBM market is still weak.

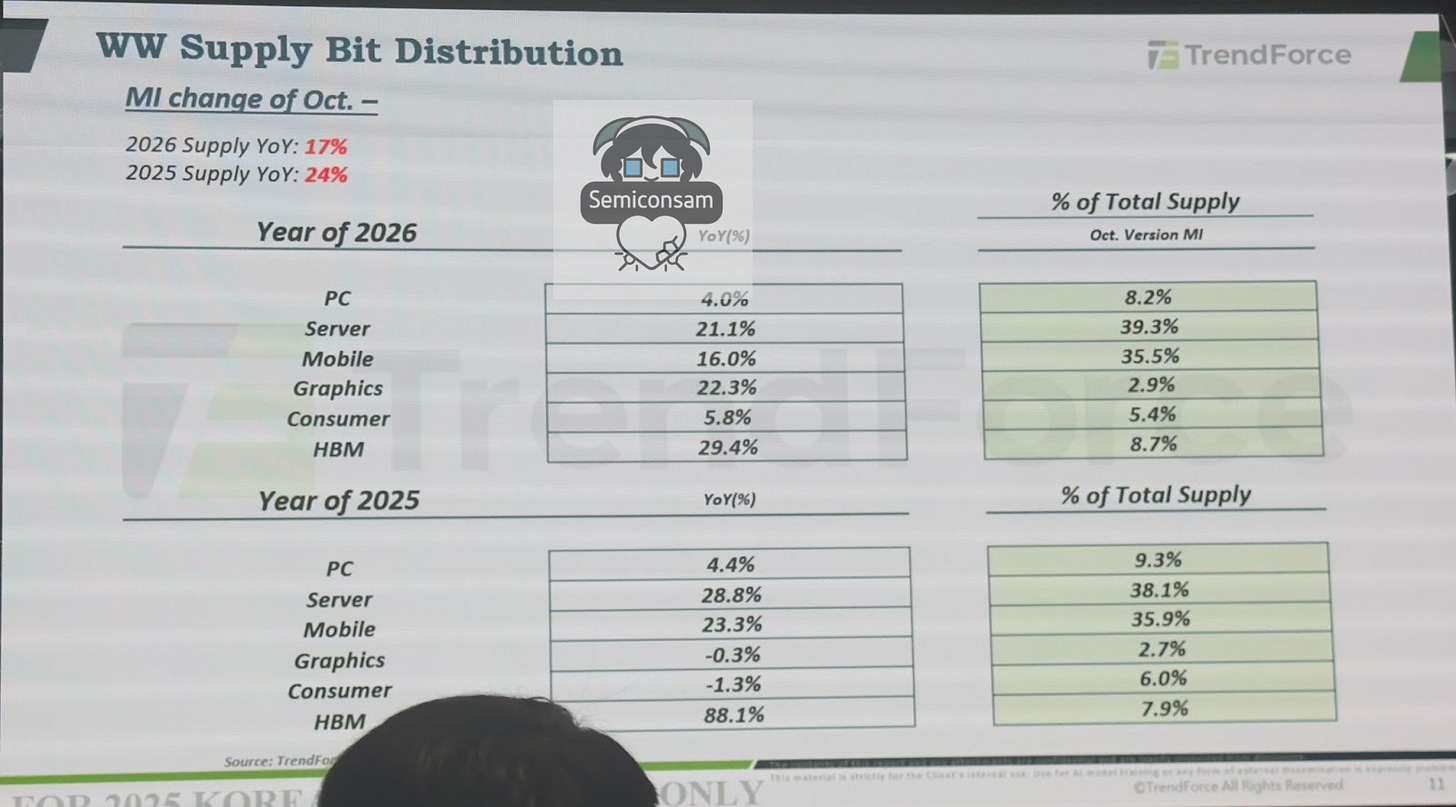

The growth in graphics DRAM is noticeable.

It seems a bit early for this to be driven by Rubin CPX…

Perhaps this is being influenced by the RTX Pro 6000 refresh cycle?

The slowdown in HBM demand also stands out.

However, I don’t think there is much need for concern here.

The main reason is that Blackwell Ultra and Rubin have similar HBM capacity configurations, which temporarily dampens incremental HBM demand.

This should not be interpreted as weakening demand for HBM itself.

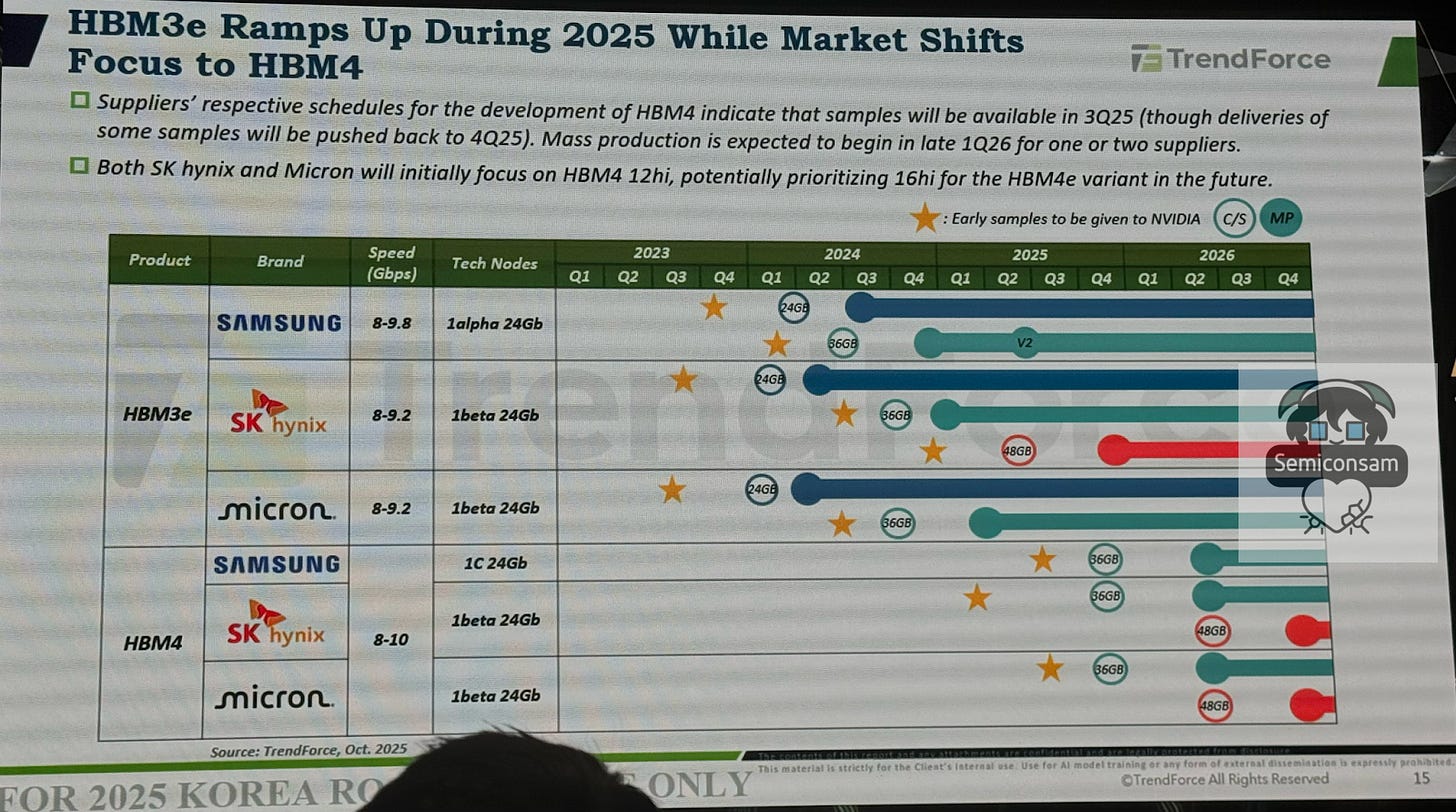

In this table, the following can be read:

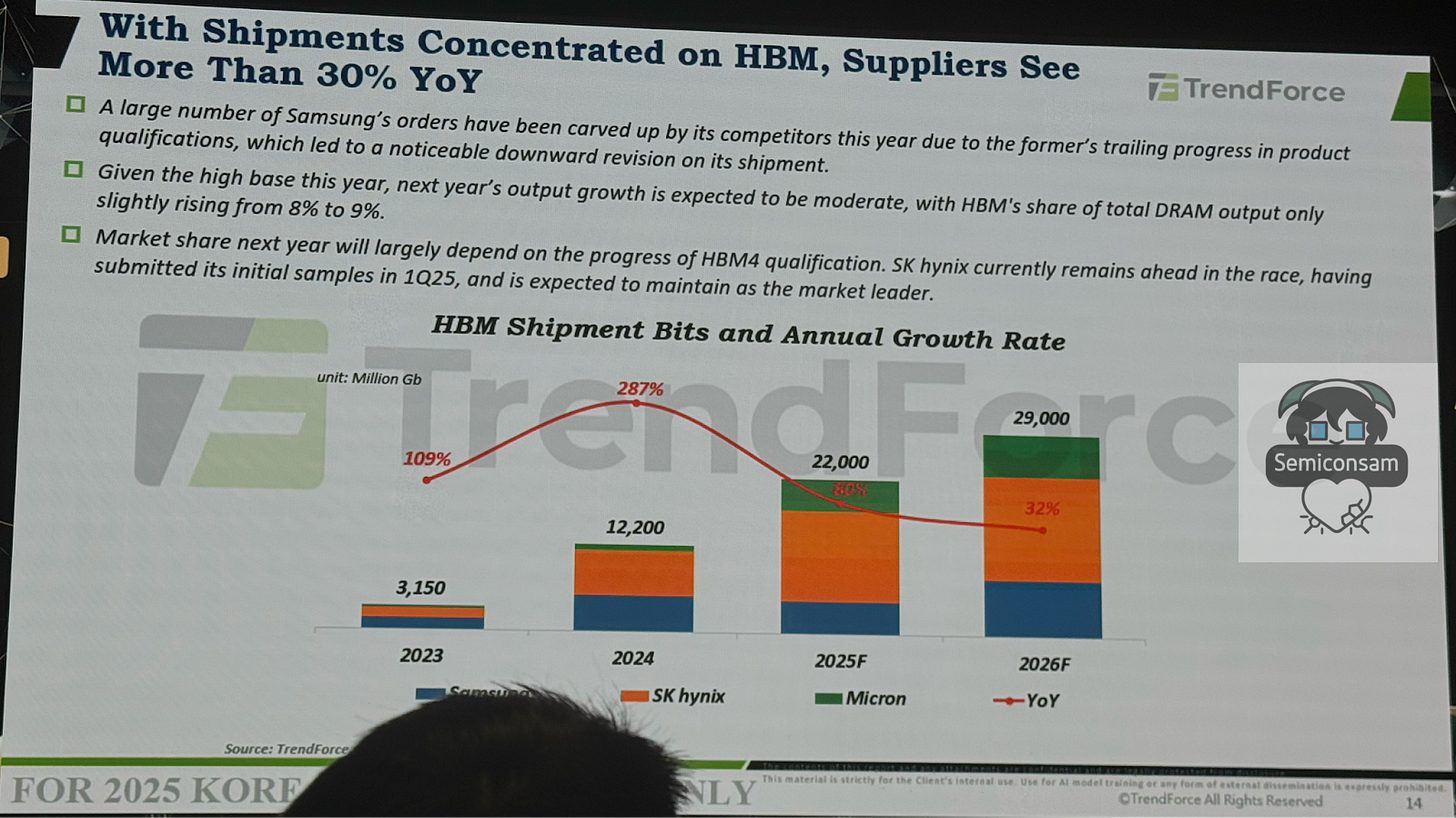

Samsung achieved almost no growth from HBM in 2025.

However, in 2026 it will grow in HBM by about 9–11%.

SK hynix achieved tremendous growth in HBM in 2025.

However, this HBM growth is expected to partially slow in 2026.

Instead, to the extent of that slowdown and more, it will grow in general-purpose DRAM.

Micron grew in HBM in 2025 more than SK hynix.

Micron will grow the most steeply among the three.

CXMT is aggressively increasing its growth rate to achieve economies of scale.

Additional comment: Existing DRAM = process miniaturization (Technology): achieving higher output per wafer (bit density) by shrinking processes in existing fabs—e.g., to 1-alpha (SK hynix) and 1-gamma (Micron)—without building new fabs.

TrendForce is harshly critical of Samsung, lol.

It seems right to say that SK hynix captured most of the gains from HBM growth in 2025.

One interesting point is that TrendForce appears to think SK hynix will also take the lead in HBM4.

As evidence, they point to SK hynix being the first of the three memory makers to provide samples.

However, I can’t help thinking they may be underestimating Samsung.

I believe Samsung will take roughly 30% of the HBM4 market next year.

I’m also hearing from inside sources that Samsung internally is very confident about HBM4’s performance.

This table contains quite a few important points.

First, TrendForce expects SK hynix to mass-produce 16-high HBM3E.

This is also the first time I’m hearing this. As far as I know, 16-high HBM3E has been at the sample level for technology demonstration.

It may be that someone on the ASIC side (perhaps Google?) requested 16-high HBM3E.

Second, TrendForce sees no delay for Micron’s HBM4.

In other words, they regard the GF report I shared on X a few days ago as not factual.

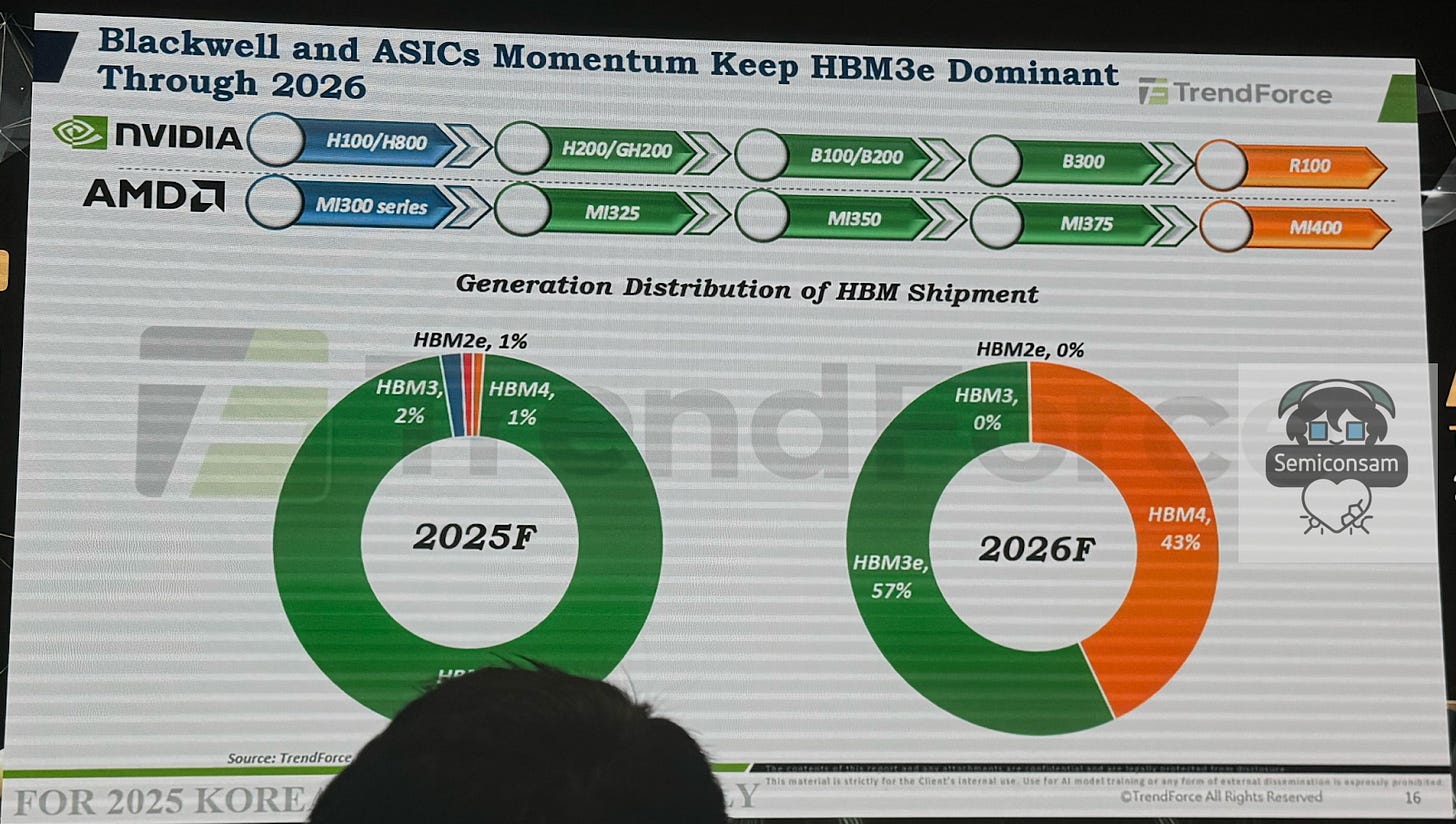

The view that HBM3E will be the best-selling HBM product even in 2026 has been around for some time.

However, in the material I just reviewed, the projected share of HBM4 within total HBM sales in 2026 was more aggressive than any sell-side estimate.

In other words, isn’t TrendForce implicitly suggesting that Rubin is being pulled forward?

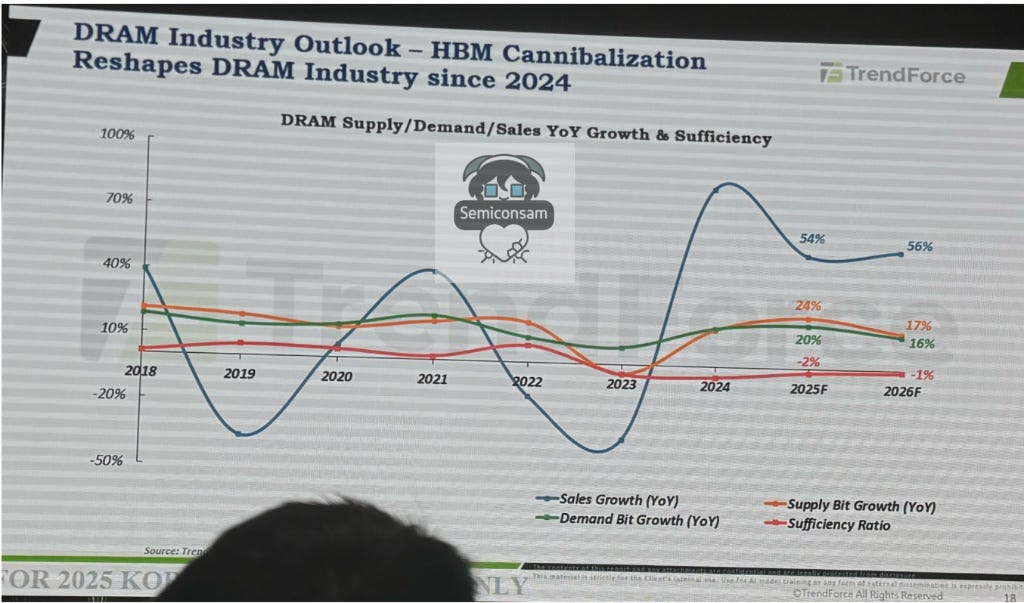

DRAM is expected to sustain a higher revenue growth rate in 2026 compared to 2025.

What stands out is the projection that the market will continue to suffer from chronic supply shortages in 2026 as well.

This is because HBM wafer demand continues to eat into general-purpose DRAM wafer allocation, keeping supply persistently tight.

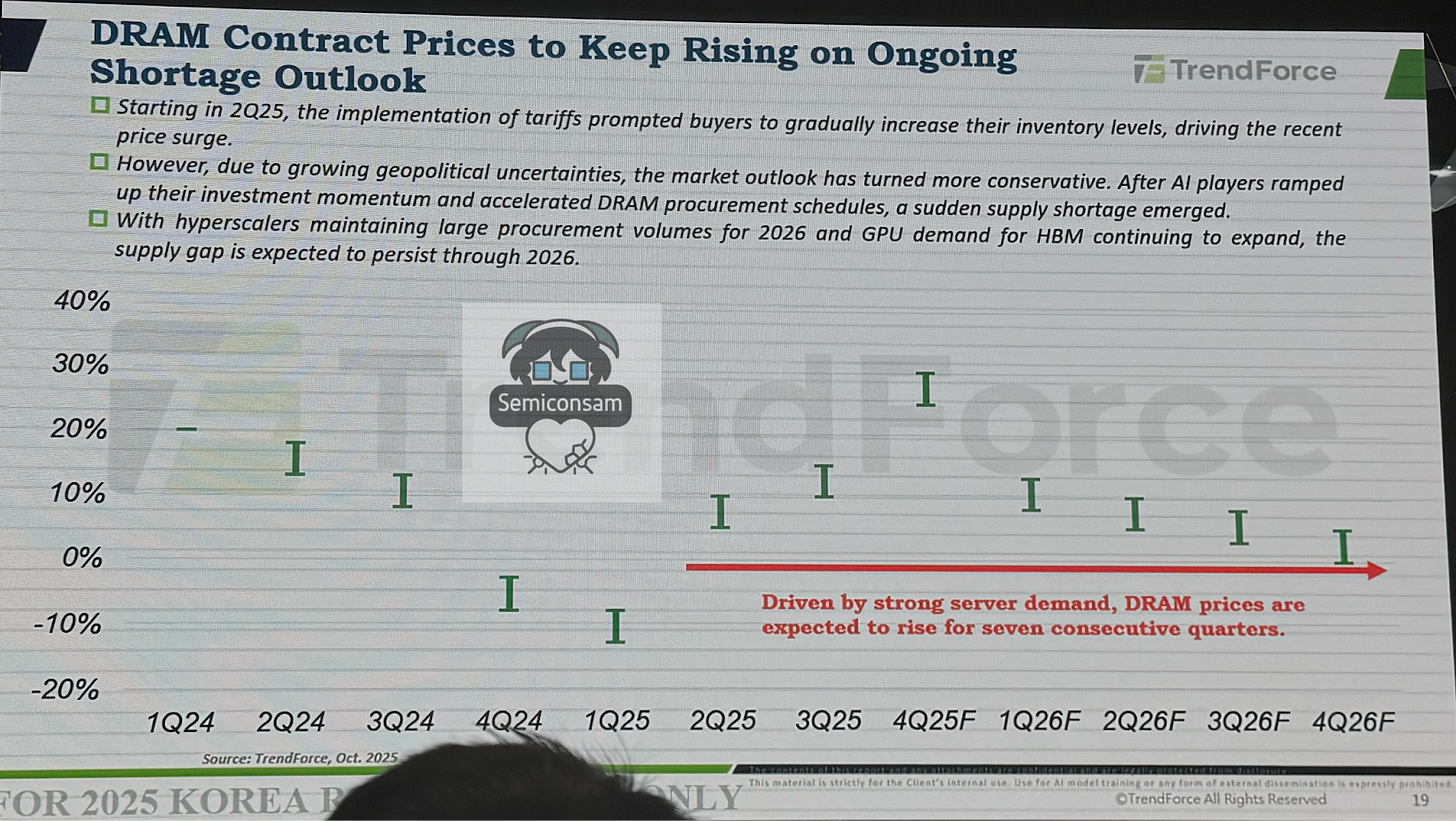

Really interesting material.

In the fourth quarter of 2025 alone, a price increase of roughly 30% for DRAM is expected…

This means I’m very much looking forward to the Q4 earnings of SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron.

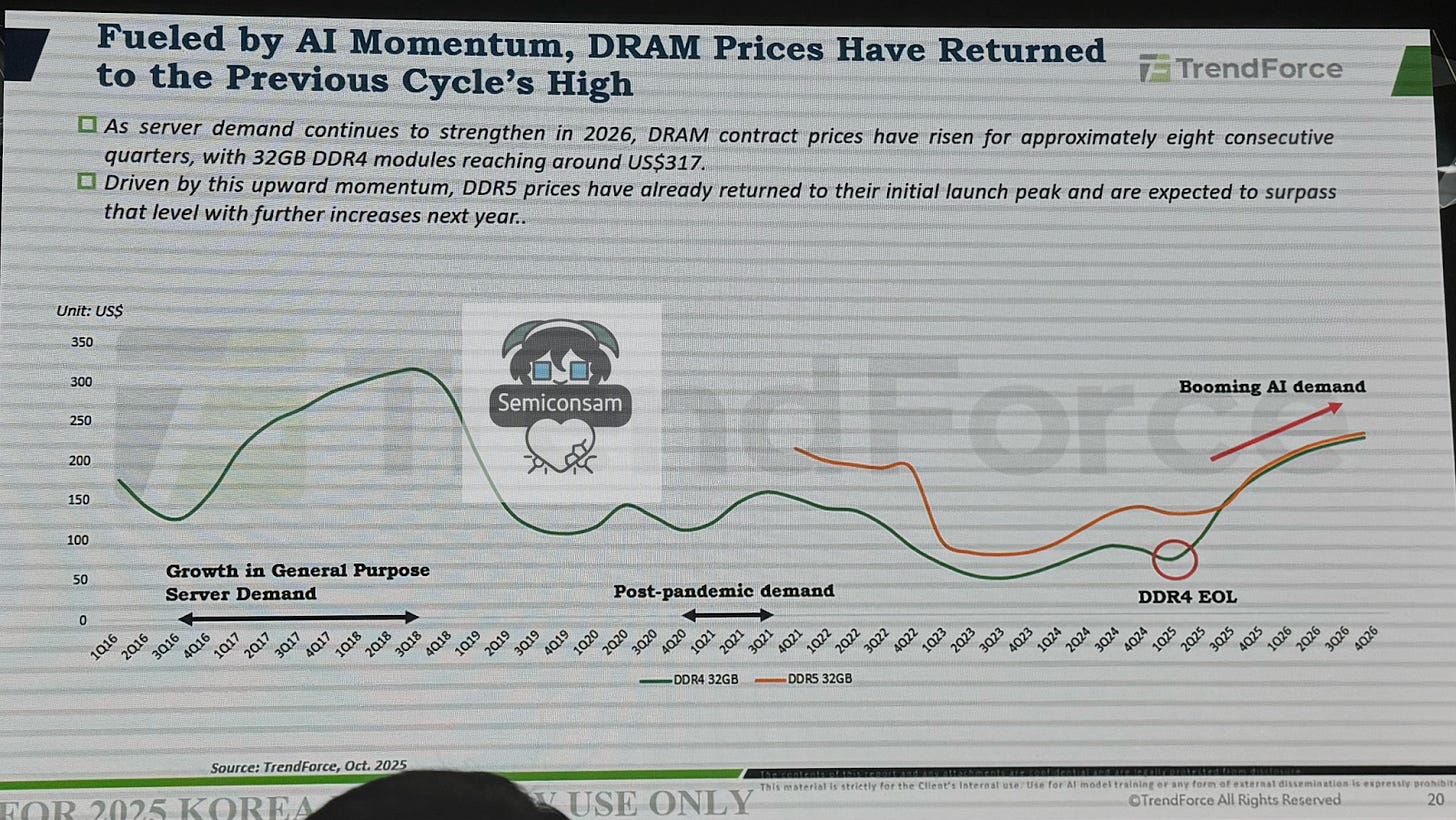

Another noteworthy point is that prices are projected to continue rising through the fourth quarter of 2026.

This is the longest upcycle in the history of the DRAM industry.

“DDR5 prices have already recovered to their initial launch peak, and are expected to surpass it next year.”

Normally, when a product reaches EOL, demand collapses and prices plunge as it gets replaced by newer products like DDR5.

But look at the chart. Even DDR4 (the green line), which has already been declared EOL, begins to surge sharply again starting in 2025.

Isn’t this the strongest evidence of HBM cannibalization?

Manufacturers are halting DDR4 production to allocate their limited DRAM production lines to HBM and DDR5. As a result, despite being an EOL product, supply to support legacy server demand disappears, creating the bizarre situation where even “older products” are experiencing price spikes.

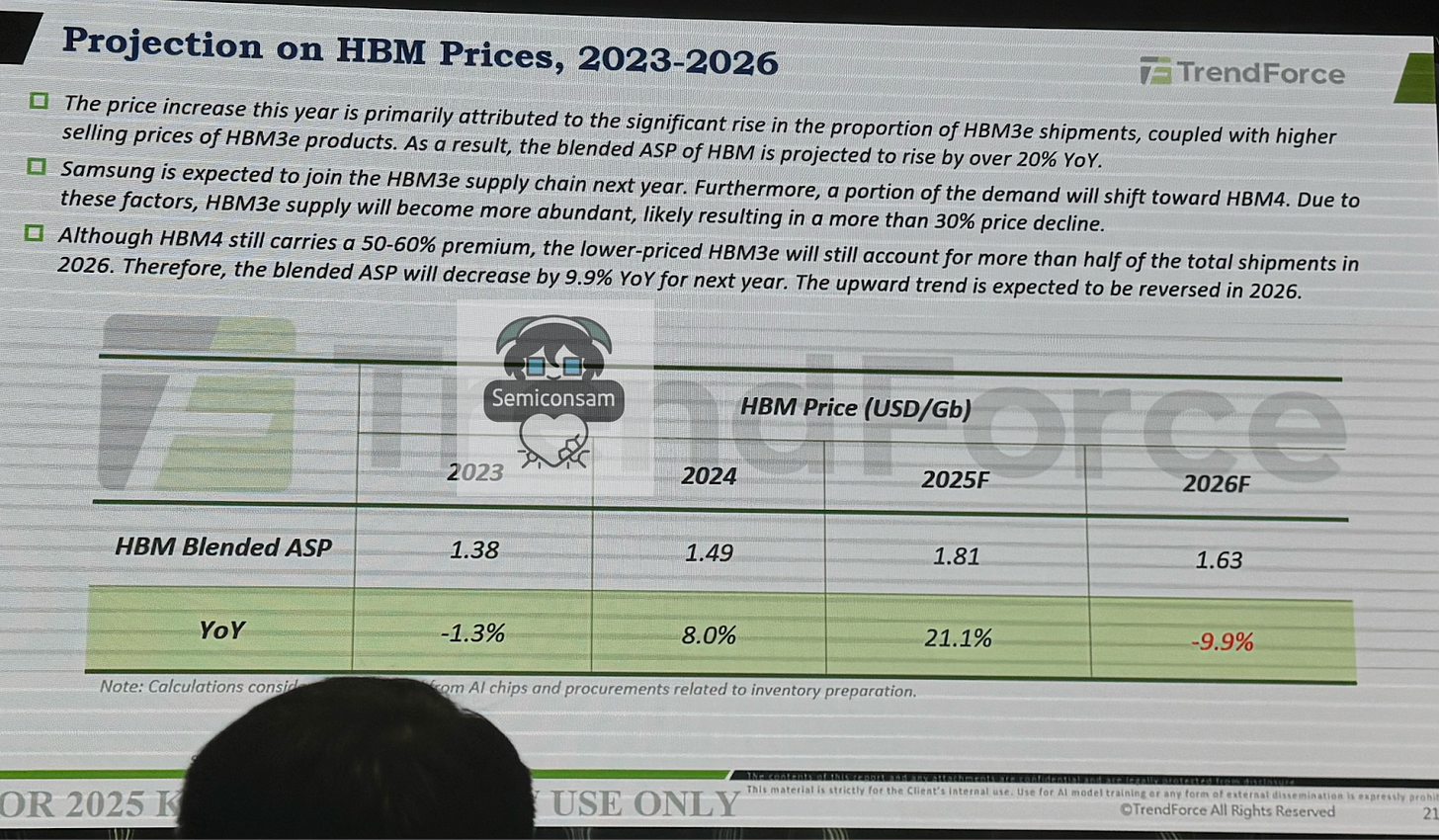

Samsung is expected to join NVIDIA’s HBM3E supply chain next year, which means HBM3E prices are projected to decline by around 30%.

HBM4 will command a 50–60% price premium compared to HBM3E.

However, since the majority of HBM sold in 2026 will still be HBM3E, a decline in HBM3E ASP is unavoidable.

Jukan’s view:

A somewhat disappointing estimate.

Some sell-side houses had published reports reflecting the expectation that HBM3E prices would fall less, due to the ongoing supply shortage (there were rumors that Samsung would divert some of its general-purpose DRAM capacity to HBM3E production).

However, TrendForce seems to see it differently.

According to sources familiar with the matter, Samsung will indeed join NVIDIA’s HBM3E supply chain, but the volume will not be large. And even that comes with the condition that Samsung must buy back the Blackwell systems that use its HBM3E…

It feels like TrendForce’s projection may be overly conservative.

Jukan’s view:

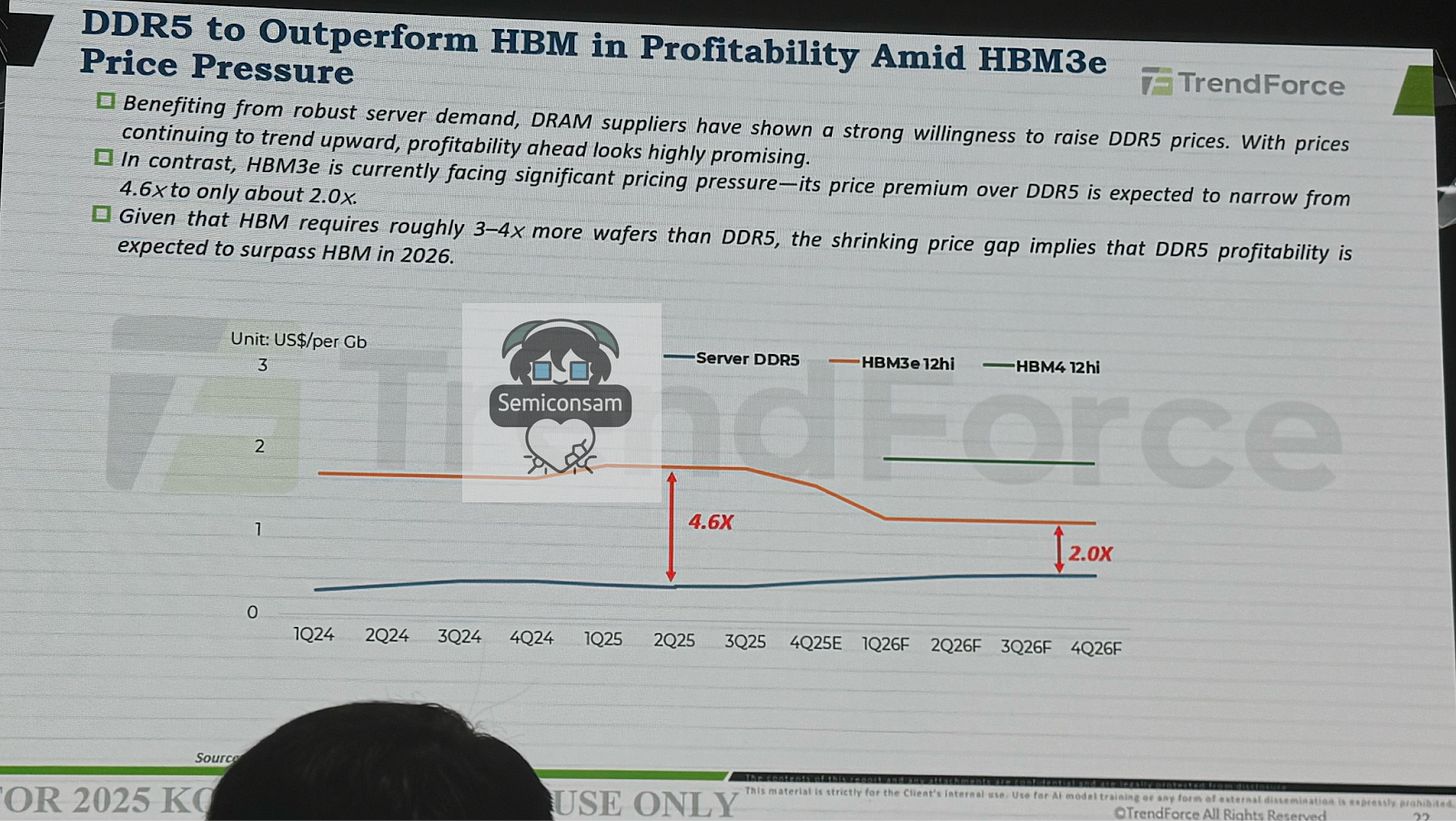

HBM3e (orange line): Prices are expected to peak in 1Q25 and then begin to decline, falling nearly 40–50% by the end of 2026 compared to early 2025.

Server DDR5 (blue line): Supported by solid server demand, prices are expected to either slightly increase or remain stable.

Result: The price gap between HBM3e and DDR5 narrows sharply from 4.6x in 2Q25 to 2.0x in 4Q26.

Here’s the interesting part: HBM requires about 3–4× more wafers than DDR5.

This implies that the COGS of HBM is 3–4× higher than that of DDR5.

Combining these two points:

The price premium begins to fall below the cost premium.

In other words, starting in 2026, selling DDR5 becomes more profitable than selling HBM from a margin perspective.

The recent rumors that Micron may shift capacity from HBM back to server DRAM are likely related to this.

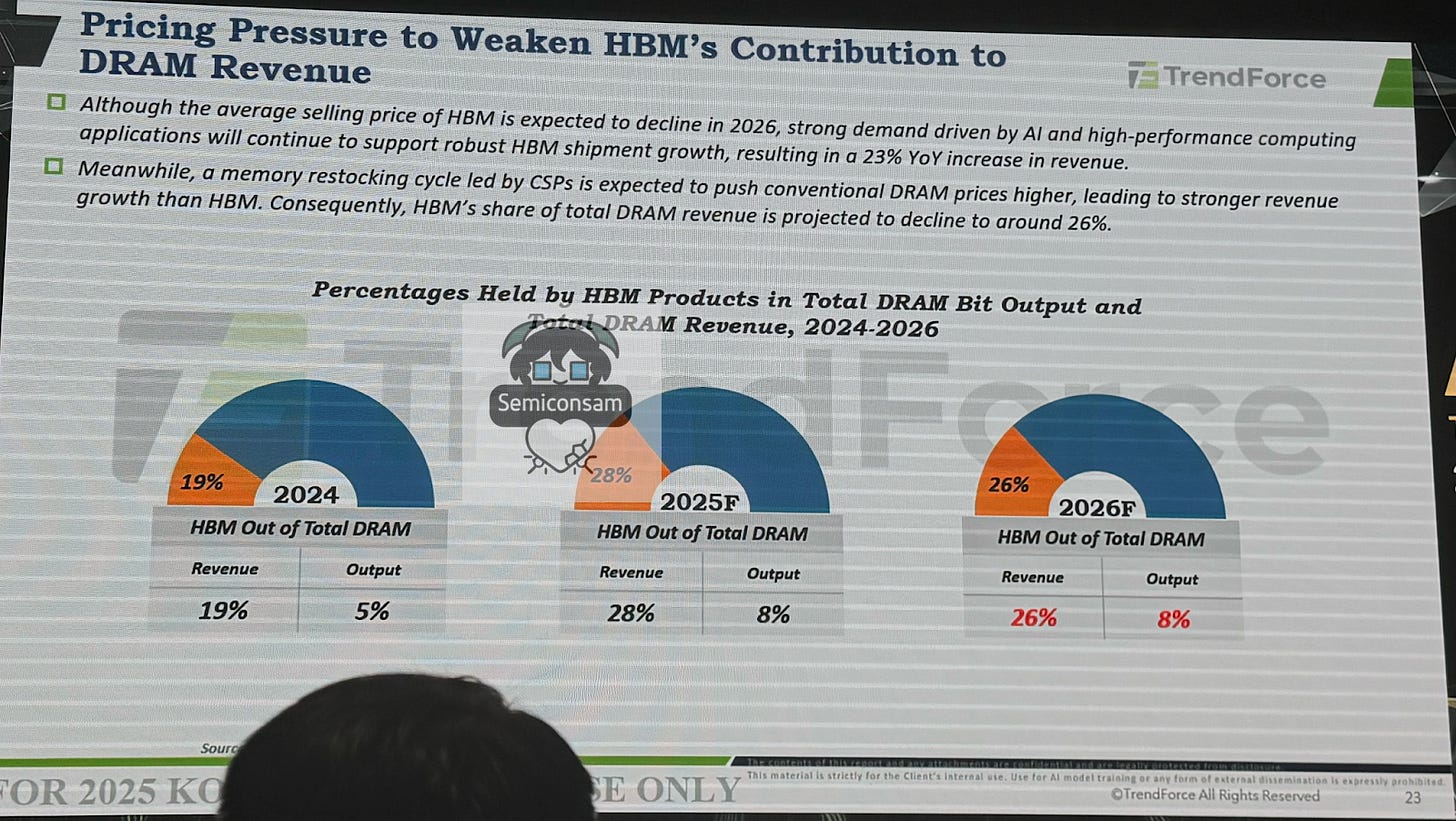

The share of HBM output as a percentage of total DRAM remains at 8% in 2026, the same as in 2025.

However, its revenue contribution is projected to decline to 26%.

This once again reminds us of the ASP decline for HBM3E mentioned earlier.

Alternatively, it could be interpreted as general-purpose DRAM prices rising more sharply, leading to faster revenue growth on that side.

It can also be seen as a signal that the era in which SK Hynix effectively monopolized HBM is ending, and that competition—at least to some extent—has begun.

The memory section ends here.

Let’s move on to the foundry section next.

The memory session is provided for free, while the foundry session is behind a paywall.